Itinerary

![]() Educational Dossiers

Educational Dossiers

Itinerary

|

From November 21th, 2007 to March 3rd, 2008 Galerie sud

|

|

|

View of the exhibition © Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian |

THE BEGINNINGS

PUBLIC (PUBLIC SPACES)

LEGIBILITY

TRANSPARENCY

URBAN (URBANISM)

LIGHTNESS

ENVIRONMENTAL (ECOLOGY)

SYSTEMS

WORKS IN PROGRESS

LIST OF PROJECTS AND COMPLETED CONSTRUCTIONS PRESENTED IN THE EXHIBITION, CLASSIFIED BY THEME.

The Centre Pompidou, which is celebrating its thirtieth birthday this year, welcomes its first retrospective exhibition dedicated to Richard Rogers. It was a decisive moment in his career when the British architect and his Italian colleague Renzo Piano won the big international competition for the design of this centre for art and culture. In a career spanning forty years, Rogers has developed a major body of work in which technical mastery, social awareness and urban thinking are combined.

Through fifty or so projects and creations, the aim of the Richard Rogers + architects exhibition is to demonstrate the contribution and inventiveness of this production, using a thematic approach focusing on the key concepts of his practice: “Transparency”, “Legibility”, “Public”, “Systems”, “Urban”, “Environmental” and “Lightness”.

Presented in the Galerie sud, free of partitions and glazed on three sides, in conformity with the Centre Pompidou’s basic principles of transparency and interpenetration, the exhibition is designed like a city within a city. Projects and completed works are assembled on tables forming irregular islets corresponding to the themes which become the different sectors of the city. In addition to these themes, supported by “iconic creations”, there is at the entrance an islet devoted to the architect’s beginnings, and on the periphery a sector under construction: projects currently in progress.

In each islet, scale models and photographs have been given priority for presenting the practice’s work. Light fittings designed by the architect contribute additional lighting complementing the abundant natural light. A network of small streets and wider avenues enable the visitor to move from project to project and from theme to theme, while at the centre of the installation a piazza is left free, echoing the piazza outside, in front of the building, that gives breathing space to the neighbourhood.

The first islet, situated at the entrance to the exhibition, presents the period at the beginning of the architect’s career, during which, nourished by his work in collaboration with others, he established his constructive thinking and affirmed his interest in the notion of flexibility.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

The prototype of the Zip-Up Houses (“ready-to-assemble”) is emblematic of this time. Devised by Richard and Su Rogers, the concept consisted in the prefabrication of façade panels enabling the interior space to be arranged independently of the structure. Far from creating standardised housing, it enables the inhabitants, at least expense, to design and modulate their interior space at their convenience. It was with this same perspective that the house of Nino and Dada Rogers was constructed.

House of Nino and Dada, London

On a long narrow plot, the house that Richard Rogers built for his parents is divided into two sections, the living quarters and the lodge, separated by a garden. The transparent façades play with the limits between the interior and exterior, integrating the garden into the architecture.

Using a structure of steel portals (five for the house and three for the lodge), the interior space is completely free. The partitions are modular and portals can be added to extend the constructed space, reclaiming space from the interior garden, for example. Richard Rogers presents this construction as “a flexible and transparent tube”.

Public spaces, reflections of the societies that enliven them and places for urban self-expression, are at the heart of the architectural problematic. For forty years, the creation of buildings which bring life to the neighbourhoods in which they are situated and which allow the dynamic nature of society, in all its diversity, to be expressed, has been one of the Rogers practice’s highest priorities. Several projects of the Rogers partnership bear witness to this endeavour, allowing open spaces and streets to enter into the constructed area.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

That of the Rome Congress Centre (1999, unbuilt project) is a perfect illustration of this attitude of openness towards the city: the half-buried volume of the auditorium and the restaurants is covered by a sloping slab connected to the street, which is itself dominated by the volume of the conference and exhibition rooms. The public space enters into the building, thereby participating in and contributing to the activities taking place there. Ten years earlier, the project for the Tokyo International Forum competition (1990, unbuilt project), with its auditoriums suspended from steel portals, was also designed as an uninterrupted public space. However, the Centre Pompidou, the most emblematic of projects demonstrating the penetration of the city into architectural design, dates from the early years of the architect’s career.

The Centre Pompidou, Paris

In 1969, the French president Georges Pompidou launched a project for a grand national centre for art and culture in the historical centre of Paris, which would house a national modern art museum, a public reference library, an institute for research and coordination in acoustics and music, and a centre for industrial design. A project of such ambition demanded the organisation of an important international competition in which 700 teams participated, among them that formed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers.

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, 1971-1977

Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, 1971-1977

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The project submitted by the two architects attracted the attention of the jury for several reasons. Their proposal for this building, designed in a playful spirit, consisted of large unencumbered superimposed floor plates enabling a mixture of different types of activity, encouraging the modularity of spaces and favouring the meeting between the general public and contemporary creation in all its forms.

However, the decisive point that justified the jury’s choice was their proposal to leave a vast space freely available to the public in front of the building: the piazza. This piazza, providing breathing space for the densely populated neighbourhood, continues into the building as the forum, a sort of covered public square with neither steps nor thresholds to separate it from the exterior, with a façade entirely of glass that insists on the continuity between inside and outside. The public space continues vertically with the caterpillar, the huge escalator suspended from the façade, conceived as a new thoroughfare offered to the city.

For further information about the building: see the Educational Dossier Découvrir l'architecture du Centre Pompidou (Discover the architecture of the Centre Pompidou, French only)

The notion of legibility refers to buildings which express, in their very forms, the manner in which they have been constructed, what keeps them standing and how they function. Legibility thus renders visible and identifies the activities taking place inside. Legibility forces the concrete interaction of the building’s functions with its architecture. A “legible” building is finally one which, far from being anonymous and opaque, allows itself to be apprehended and decoded by the public.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

In the Kabuki Cho Tower (1987-1993), the partnership’s first construction in Japan, the stairs and lifts fixed to the exterior and the glazing designed to capture the daylight give the construction its identity. It is however with the headquarters of Lloyd’s, in London, that the notion of legibility is undoubtedly best expressed.

The Lloyd's of London Building

In the year following the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou, the Richard Rogers Partnership, recently founded by the architect, was selected by Lloyd's of London to build its new headquarters. On the advice of Gordon Graham, then president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), it was a matter of “working on a strategy of development even before thinking about the architecture per se. “ This is where the specificity of this project, developed by the team in collaboration with the institution, lies. This international insurance market, established in the City since 1928, needed a workplace that was flexible, capable of responding to growth and symbolic of its dynamic reputation.

The Lloyd's of London Building, United Kingdom, 1978-1986

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The Partnership’s architects and engineers centred the construction around an atrium of 14 floors topped with a glass roof. Around the atrium are the floor plates accommodating the subscription rooms on several levels. Finally, on the periphery of this ensemble, six service towers made of steel modules are connected to the building by the “clip-on” concept. This exteriorisation of functions enables the activity surfaces inside to be freed of all constraints and to facilitate, outside, the insertion of the building into the sinuous urban fabric of the mediaeval City. It also contributes to the symbolic impact of the construction: here, the mechanical aesthetic replaces the traditional monumental architectural codes. The functions are displayed and can be read on the façade, thereby contributing to the identity of the building. The Lloyd's of London Building, completed in 1986, has thus become the emblem of the modern city.

Also evoking the idea of the visibility of structures and activities, the notion de transparency may seem to blend with that of legibility. It is, however, a very specific reference, inscribing the work of Richard Rogers in the great modern architectural adventure of glass and light, which together form the building and play with the relations between interior and exterior.

According to Rogers, transparency in architecture “is comparable to the concept of transparency in the organisation of a society, and therefore to democracy and openness, to the rupture of ancient hierarchies traditionally hidden behind masonry walls.”

In the 88 Wood Street office building in London (1991-1999), the interior lighting emphasises, at night, the articulation of the entirely glazed façades, which, during the day, allow the sky to be seen through the building. While many of Rogers’ designs draw on this notion of transparency, the Channel 4 building is the perfect illustration.

Channel 4 Television Headquarters Building, London

This building constructed for the British television company is situated on the major urban axis of Victoria Street, not far from the Houses of Parliament and Westminster Abbey. It is composed of two entirely glazed wings, which accommodate the offices and production studios, forming a right angle, with the main entrance in the middle.

Channel 4 Television Headquarters Building, London, United Kingdom, 1990- 1994

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The interesting feature of the building is the treatment of this angle. It is effectively designed as a concavity, leaving a circular space in front of the entrance which is prolonged by an atrium, with a structural glass[1]façade suspended from beams. It thus causes the building to communicate with the city, and by transparency links the exterior space to the garden situated behind, in the heart of the plot.

Around this central curve, on the gables of the two wings, are located conference rooms on one side and, on the other, the lift wells, topped by a television antenna which serves both as a sign and transmitter. Entirely glazed, these spaces symbolise the dynamic nature and activity of the company which are thus displayed to the street.

[1]Structural glass enables the construction of façades entirely of glass, without a chassis.

The importance that Richard Rogers places on detail, on fragments of architecture, is combined with a way of thinking that is on the scale of the city. The answer to social and ecological questions lies, according to Rogers, in the development of “compact cities with multiple centres”, blending residential units with workplaces, accommodating rich and poor, young and old, and favouring the circulation of pedestrians, cyclists and public transport.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

Present from the time of the conception of the Centre Pompidou, this interest in the urban dimension was embodied in the development, in 1986, of the London as it could be project. Created in the context of an exhibition, this plan, with its futuristic aesthetic features, places the Thames at the centre of the city’s development. In opposition to the prevailing ideas of the time, Rogers insisted on the enhancement of public spaces and placed architecture in a political and social vision of the city. Since 2000, Richard Rogers has given new impetus to this commitment through his collaboration with the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. The plan for the Lu Jia Zui district, in Shanghai (unbuilt), also belongs to this search for solutions for thinking the modern city.

Lu Jia Zui, Shanghai

The Lu Jia Zui district, in the Pu Dong sector isolated from the centre of Shanghai by a bend in the Huangpu river, was the subject of a renovation project in the early 1990s to accompany the demographic explosion and economic boom the city was then experiencing. The Richard Rogers team was one of six teams invited to design a masterplan for the district.

Lu Jia Zui masterplan, Shanghai (Pu Dong), China, 1992-1994 (unbuilt)

Lu Jia Zui masterplan, Shanghai (Pu Dong), China, 1992-1994 (unbuilt)

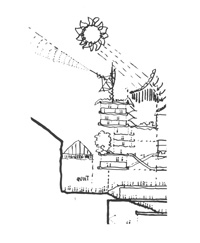

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The solution they proposed is based on a circular configuration around a central park, with a general structure of varying heights that optimises access to daylight while creating open perspective angles to the river and the city. From the park just six main road axes radiate out, the major part of the network giving priority to the circulation of pedestrians and cyclists in the district, and public transport to access the city centre. To facilitate local movement, the constructed islets are a blend of residential, commercial and office buildings. The model proposed by the practice, and which in the end was not selected, is one of a district that is simultaneously dynamic, pleasant and ecologically responsible.

Laying claim to the heritage of 19th Century railway stations and the geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller, the Rogers practice is anchored in two centuries of history and upheld by the endeavour to “enclose space at the least expense”. The notion of lightness is a key concept of its work, based on close collaboration between architect and engineer, a notion which is often combined with those of transparency, legibility and architecture-system.

The creation of structures founded on the concept of economy of materials and means enables the architect to satisfy the needs of clients at the least expense and with elegance, as evidenced by the suspended structure of the Fleetguard Factory (1979-1981), the central portal frame supporting the roof of the INMOS Factory (1982-1987), or the floating roof suspended from two steel masts dominating the glass walls of the Michael Elias house (1991, unbuilt). The Millennium Dome, through the achievements it entails, is the emblematic work of this notion of lightness.

Millennium Dome, London

The Greenwich Peninsula in London, on which the Millennium Dome is implanted, was until the 1980s the site of one of Europe’s biggest gas refineries. In the 1990s, the site became the subject of a huge project of decontamination and redevelopment, entrusted to the Rogers Partnership in 1996. At the same time, the site was chosen for the celebrations to mark the passage into the new millennium.

Millenium Dome, London, United Kingdom, 1996-1999

Millenium Dome, London, United Kingdom, 1996-1999

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

At the time, the team proposed the construction of a dome, initially conceived as temporary then rendered permanent by a government decision at the end of 1997. Completed in 1998, the dome is a simple tent-like structure consisting of steel masts, a network of cables and a Teflon-coated envelope covering an area of 100,000 square metres with a central height of 50 m. The Millennium Dome is a fine example of technical prowess combined with economy of means, rapidity of execution and flexibility of usage. It belongs as much to the world of nomadic constructions as it does to the monument, to engineering as much as to architecture.

Because they build the cities of tomorrow, architects are among the main protagonists concerned in the battle against global warming and in favour of sustainable development. Accordingly, the Rogers agency places ecology at the heart of its work, giving priority to renewable energies in the production and operation of its creations.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

The National Assembly for Wales (1999-2005), with its natural ventilation, its biomass heating and its rainwater harvesting system, is a model of the genre. Situated in a disadvantaged neighbourhood of London, the Mossbourne Community Academy (2002-2004) (in total harmony with the policy of urban renovation maintained by Rogers in collaboration with the municipality) has also been designed, with its wooden skeleton and six ventilation towers, with a concern for environmental respect. Many other projects and creations exemplify the environmental commitment of Richard Rogers and his team. Designed in the early 1990s, the Bordeaux Law Courts can be considered their manifesto in this domain.

Bordeaux Law Courts

Built on an historic site in the city of Bordeaux, marked by the presence of vestiges of its ancient ramparts, the law courts building is a key structure in the evolution of the practice’s thinking. The building is in keeping with a philosophy that seeks the parallel between the necessary transparency of justice and that of architecture, resulting in a construction that is open and accessible. A copper roof assembles the highly fragmented structure: opposite the glazed parallelepiped administrative section and joined to it by bridges is the alignment of the seven courtrooms. Clad in wood, the courtrooms are cone-shaped structures that are raised on concrete pilotis and extend up into the roof. The space beneath the courtrooms is accessible to the public.

Bordeaux Law Courts, France, 1992-1998

Bordeaux Law Courts, France, 1992-1998

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

The complex addresses environmental concerns. The zenithal opening of the courtrooms provides natural lighting while their curved shape facilitates ventilation since they function like extractor hoods. In addition, the wooden construction calls on local resources and know-how. In fact, the company that assembled the structures used the traditional techniques for making wine vats. The conception of the building in small volumes separated from each other and elevated allows better air circulation and savings in terms of heating and lighting costs. Finally, the copper roof captures heat, which is stored in the concrete base.

The notion of architecture-system is fundamental to Rogers’ work, which as a result has sometimes been reduced to the expression of a “high-tech style”. While there is no question that there exists an aesthetic of function in his work, which is found in the concept of legibility, it is never an idle gesture. The aim of these constructive systems, which employ new technologies and modern materials, is prefabrication and the application of mass production to architecture which enables flexibility, efficiency, low production costs and construction site savings.

In 1992, a competition launched in South Korea for a programme of industrialised housing offered Rogers an opportunity to return to the research he carried out earlier in his career. In a reversed “clip-on” process, the service and circulation structures which, as in the Lloyd's building, are connected to the building, are here gathered into a central concrete nucleus onto which are affixed residential units of pressed steel (unbuilt). The recently completed Terminal 4 of Barajas Airport in Madrid is the icon project for this theme in the exhibition.

Terminal 4 of Barajas Airport, Madrid

The construction of an airport terminal is an exercise in which the numerous constraints in terms of circulation and lighting must be taken into account. To address these concerns at Terminal 4 of the Madrid Airport, the practice devised a system of “canyons”, stretching across the three levels of the superstructure from top to bottom, and aligned throughout the length of the terminal.

Terminal 4 of Barajas Airport, Madrid, 1997-2005![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

Covering the complex, the undulating roof, like “an invitation to a dream and to a voyage”, becomes the main façade of the site. Far from being the result of an aesthetic endeavour, this roof was designed to address the constraints of the terminal, to favour lighting and ventilation and to provide a surface for rainwater harvesting. The roof is constructed from the one module used repetitively. Designed with computer assistance, the module enables a combination of strength, economy and ease of assembly.

Since the architect’s first constructions in the late 1960s and throughout many years of collaboration, the practice, recently renamed Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners has incessantly grown and extended the scope of its activities. With a staff of close to 200 people, and the adoption of the original format of a foundation, the practice is currently conducting numerous projects all over the planet.

![]() View of the exhibition

View of the exhibition

© Centre Pompidou - Photo Georges Meguerditchian

Among these are the conversion of the Barcelona arenas into a leisure and culture complex, an operation for residential accommodation in Hyde Park (London) and the Jacob K Javits Convention Center in Manhattan (New York). In this group, the Tower at 122 Leadenhall Street stands out from the rest.

Leadenhall Street Tower, London

This 224.5 metre tower, presently under construction amidst the other towers of the City, faces the Lloyd's building, completed by the practice more than twenty years ago. In this environment, the tower signals its presence with its fine silhouette, which seen from the front has the shape of a long isosceles triangle pointing to the sky. Far from being a distinctive sign, this special shape is dictated by the need to preserve, in this extremely dense environment, perspective angles on the dome of the nearby Saint Paul’s Cathedral.

Leadenhall Street Tower, London, United Kingdom, 2002 (under construction)

![]() Sketch

Sketch

© Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners

In a break with the traditional concrete central nucleus, the structure opts for a tubular armature around the perimeters of the floor plates.

A tower in which service and circulation activities are grouped is affixed to the northern aspect of the main building. Finally, on ground level, special attention has been given to the building’s integration in the urban fabric: the first seven levels are recessed, which enables a tree-planted public space to penetrate into the heart of the plot.

Throughout the exhibition, guided by the vocabulary of the Richard Rogers practice, visitors are invited to explore the great wealth and impact of Rogers’ work. With new keys to reading architecture now at their disposal, visitors can continue their visit with the on-site (re)discovery of what is, in the end, the exhibition’s primary exhibit on a 1:1 scale: the Centre Pompidou itself, in which the concept of public space is put into practice, as we have seen, as well as the concepts of transparency, legibility, systems and lightness.

This retrospective is also an invitation to look more closely, in the company of a committed architect, at the challenges facing a profession that builds today the world of tomorrow.

List OF projects AND COMPLETED CONSTRUCTIONS prEsentED IN the exhibition, classIFIED BY theme![]()

(The Beginnings)

Science Campus, Yale University / Connecticut, USA / 1961 (unbuilt)

Reliance Controls electronics factory / Swindon, United Kingdom / 1967 (completed)

House of Nino and Dada Rogers / London, United Kingdom / 1968-1969 (completed)

Zip-Up Houses / 1968-1971 (prototype)

Legibility

Lloyd's of London Building / London, United Kingdom / 1978-1986 (completed)

Kabuki Cho Tower / Tokyo, Japan / 1987-1993 (completed)

Tomigaya Tower / Tokyo, Japan / 1990-1992 (unbuilt)

Chiswick Park development / London, United Kingdom / 1999-(under construction)

Transparency

Channel 4 Television Headquarters Building / London, United Kingdom / 1990-94 (completed)

88 Wood Street office building / London, United Kingdom / 1994-99 (completed)

Lloyd's Register of Shipping building / London, United Kingdom / 1995-2000 (completed)

Public

Centre Pompidou / Paris, France / 1971-1977 (completed)

National Gallery extension / London, United Kingdom / 1982 (unbuilt)

European Court of Human Rights / Strasbourg, France / 1989-95 (completed)

Tokyo International Forum / Tokyo, Japan / 1990 (unbuilt)

South Bank regeneration / London, United Kingdom / 1994-1997 (unbuilt)

Rome Congress Centre / Rome, Italy / 1999 (unbuilt)

Systems

Industrialised housing system / South Korea / 1992 (unbuilt)

Minami-Yamashiro school / Kyoto, Japan / 1995-2003 (completed)

Terminal 4 Barajas Airport / Madrid, Spain / 1997-2005 (completed)

Terminal 5 Heathrow Airport / London, United Kingdom / 1989-2008 (completed)

Bodegas Protos winery / Peñafiel, Spain / 2003-2008 (under construction)

Environmental

ARAM Module / undefined site / 1971 (unbuilt)

Nottingham Inland Revenue Headquarters / Nottingham, United Kingdom / 1992 (unbuilt)

Bordeaux Law Courts / Bordeaux, France / 1992-1998 (completed)

Daimler Chrysler office and residential buildings / Berlin, Germany / 1993-99 (completed)

Antwerp Law Courts / Antwerp, Belgium / 1998-2005 (completed)

National Assembly for Wales / Cardiff, Wales / 1999-2005 (completed)

Mossbourne Community Academy / London, United Kingdom / 2002-2004 (completed)

Potsdamerplatz and Leipzigerplatz masterplan / Berlin, Germany / 1991 (unbuilt)

Coto de Macairena urban planning / Granada, Spain / 2004-(under construction)

Valladolid Alta Velocidad urban planning / Valladolid, Spain / 2005-(under construction)

Urban

Coin Street development / London, United Kingdom / 1979-83 (unbuilt)

“London as it could be” Exhibition / London, United Kingdom / 1986 (unbuilt)

Lu Jia Zui masterplan / Shanghai (Pu Dong), China / 1992-1994 (unbuilt)

Lightness

Fleetguard production and distribution centre / Quimper, France / 1979-81 (completed)

INMOS microprocessor factory / Newport, Wales / 1982-87 (completed)

Michael Elias House / Los Angeles, California / 1991 (unbuilt)

Saitama Complex / Omiya, Japan / 1995 (unbuilt)

Millennium Dome / London, United Kingdom / 1996-99 (completed)

(Future, works in progress)

Transbay Tower and transport terminal / San Francisco, USA / 1998-2007 (unbuilt)

Conversion of the Barcelona arenas / Barcelona, Spain / 2000-(under construction)

Leadenhall Street Tower / London, United Kingdom / 2002-(under construction)

Residential buildings 1 Hyde Park / London, United Kingdom / 2004-(under construction)

Key Worker housing / London, United Kingdom / 2004-(under construction)

Jacob K Javits Convention Centre / New York, USA / 2005-(under construction)

Design for Manufacture housing / Milton Keynes, United Kingdom / 2005-(under construction)

Aerospace Campus / Toulouse, France / 2007-(under construction)

Website - Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners ![]()

Richard Rogers + Architects, exhibition catalogue, supervised by Olivier Cinqualbre, Editions Centre Pompidou, 2007 ![]()

Publications on the work of Richard Rogers and his practice

● POWELL, Kenneth, Architecture of the future: Richard Rogers, Basel, Birkhäuser, 2006.

● POWELL, Kenneth, Richard Rogers: complete works. Volume 2, London, Phaidon, 2000.

● POWELL, Kenneth, Richard Rogers: complete works. Volume 1, London, Phaidon, 1999.

● BURDETT, Richard, Richard Rogers : œuvres et projets, Paris, Gallimard-Electa, 1996. [Richard Rogers Partnership: works and projects, New York, Monacelli, 1996.]

Writings by Richard Rogers

● Des Villes pour une petite planète [Cities for a Small Planet], Paris, Le Moniteur, 2000.

● Towards an Urban Renaissance, London, Taylor & Francis, 1999.

● Toward a Strong Urban Renaissance ![]()

Works about contemporary architecture

● Atlas Phaïdon de l'architecture contemporaine mondiale [Phaidon Atlas of Contemporary World Architecture], 2004.

● CHAMPY, Florent, Sociologie de l'architecture [The Sociology of Architecture], Paris, La Découverte, 2001.

● MONNIER, Gérard, L'architecture moderne en France. 3, De la croissance à la compétition [Modern architecture in France. 3, From growth to competition], Paris, Picard, 2000.

● RAGON, Michel, Histoire de l'architecture et de l'urbanisme modernes. 3, De Brasilia au post-modernisme [History of architecture and modern urbanism. 3, From Brasilia to post-modernism], Paris, Seuil, 1991.

To consult the other dossiers on the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

Contacts

So that we can provide a service that meets with your requirements, we would like to have your reactions and suggestions regarding this document.

Contact: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

© Centre Pompidou, Direction de l’action éducative et des publics, November 2007

Text: Noémie Giard

Translated by Vice Versa Traductions

Copyreader: Olivier Rosenthal

Layout: Michel Fernandez, Françoise Sy Savane

Online dossier at www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ section on “Educational Dossiers”

Coordination: Marie-José Rodriguez

![]()