Monographs / Contemporary Artists

![]() Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

Monographs / Contemporary Artists

|

|

|

|

| Vitrine

of Reference, 1971 |

Bio

Works

• La chambre ovale (The Oval Room), 1967

• L'Homme qui tousse (The Coughing Man), 1969

• Essai de reconstitution (Trois tiroirs) [Attempt

at Recreation (Three Drawers)], 1970-1971

• Vitrine de référence

(Vitrine of Reference), 1971

• Saynètes comiques (Comic Vignettes), 1974

• Composition théâtrale (Theatrical Composition),

1981

• Les archives de C.B. (C. Boltanski Archives), 1965-1988,

1989

• Réserve (Reserve), 1990

If the plasticine, corrugated cardboard, photographs and salvaged sundries he uses would rank him at the forefront of contemporary plastic art, he himself says he has never really moved far from the traditional paintings he made when he started out. He will also contend that dexterous hands do not define art, and that religious ends and sacred power do. So Boltanski’s work can indeed fit into pictorial traditioninasmuch as it explores the religious element in art.

The sometimes almost preposterously ordinary bits and pieces he heaps

into compendia, books and collections conceal recollections that endow them

with huge emotional power. He stages them in showcases, archives, reserves

or actual exhibitions but, in every case, makes a statement about time as well

as space. Each item, in its own different way, takes us on a journey back in

time: to Boltanski’s actual, fictional, tragic or amusing past, to the item’s

past, or to humanity’s past. The items, in that sense, relics.

All these works draw us out of the present and into a place of meditatio,

or indeed even reverence in the case of pieces in recent years probing death. Even his amusing work has something caustic about it, as if he were settling

scores with incidents from his past that still haunt him. His comic works about

individual memory, his works dealing with document conservation in mu seums

or archives are about the collective memory.

So the common denominator in Boltanski’s work is memory – spanning childhood

and personal memories, memorials and the history of humanity.

Christian Boltanski (Paris, 1944)

After a patchy education and no formal training in art, Boltanski started painting

as a teenager in 1958. His early paintings were big. They depicted historical

events or, on occasion, lonely figures in macabre settings (coffins, for one).

From 1967 he started moving away from painting and exploring other

forms of expression. He started writing letters and compiling compendia, and

sending them to prominent figures in the arts scene. His raw materials were

photocopies mingled among original documents and photographs from his family

albums. Using these new materials was tantamount to investing his personal

universe in his work. To the point where his personal history grew into

one of the central themes.

The line between his life and work indeed often blurs. But not in a romantic, self-sacrificing way: Boltanski’s works are candidly amended episodes of

his own life. Boltanski rewrites incidents from a life he has never lived, using

touched-up photographs or things he has never had. He actually wrote an official

autobiography of sorts for the retrospective that the Musée national d'art moderne

organised in 1984. His life, he wrote in those memoirs, began when his calling

became patent: “1958. He paints. He wants to make art. 1968. Doesn’t buy any

more modern-art magazines, has a shock, gets into photography, black and white,

tragic, human…”. But he did more than deride the obsequious conventions of retrospective

catalogues: he prompted readers to take a new look at the point of life from

a retrospective angle.

That is why the term “individual mythology”, the title of a section

of an exhibition he took part in back in 1972, was so fitting: he told his story

as a life anyone can identify with. Or, as he himself put it, “Good artists

don’t have lives any more: their life is reduced to telling stories that others

can believe are their own.”

Today, Boltanski is acknowledged as one of

France’s foremost artists. He lives and works in Malakoff, a suburb

southwest of Paris.

![]() La chambre ovale (The Oval Room), 1967

La chambre ovale (The Oval Room), 1967

Acrylic on isorel. 115 x 146.5 cm.

On deposit, National Contemporary Art Trust, 1983. 29348

© Adagp, Paris 2007![]()

The title is one of those puns that Duchamp loved. The paintings

that Boltanski produced between 1958 and 1967 seem to spring straight from his

childhood and until-then buried past. No doubt because they conjured

up painful memories.

La chambre ovale, one of those paintings, shows a borderline-abstract

setting enveloping a forlorn character sitting on the floor, petrified and powerless

(as we can guess from the fact that he is armless).

We can somehow identify with this character’s despondency. We don’t

know if he is a prisoner or just a child in a make-believe hell. The dark, shadowlike

silhouette is what mak es the scene mysterious.

Even though this painting probably speaks of a private incident we can't understand

because we don’t know anything about it, there is something strangely familiar

in the loneliness.

This early painting already explores some of the themes that Boltanski later

held dear. All his later works are indeed experiments further down this same

road. Or, in art critic Serge Lemoine’s words, “His work is like an extension

of his painting into other techniques. But it is still nonetheless figurative,

and still tells stories about people’s lives, childhoods, families and memories.”

(Boltanski, exhibition catalogue, Centre Pompidou, 1984, p. 18).

![]() L'Homme qui tousse (The Coughing Man), 1969

L'Homme qui tousse (The Coughing Man), 1969

3-minute-long, 16-mm colour motion film with sound.

Purchased in 1975.

AM 1975-F0023.

© Adagp, Paris 2007. Dist. Light Cone (circ. Rmn).![]()

Boltanski’s first-ever personal exhibition already spoke of cinema’s pull over him. He organised that exhibition in a projection room in Paris’ 16th arrondissement, screening a film called La vie impossible de Christian Boltanski (The Impossible Life of Christian Boltanski) (1) amid life-size puppets.

After that first attempt, be produced a string of short fantasy films

in 1969. L'Homme qui Tousse was one of them.

This three-minute-long film features a man sitting in a tiny dingy room, almost

literally coughing his lungs out and literally spewing up a gush of blood

all over his clothes and down his legs. The rudimentary equipment Boltanski

used to shoot this film gives it some of its documentary feel and disturbing

effect.

He then gradually moved away from films and towards photography. But the underlying urge to explore the ambivalence between truth (the documentary element) and untruth (the fact that it is a show) remained intact.

- (1) Boltanski revisited this theme recently in a new piece, La Vie impossible (2001), a string of twenty showcases displaying photographs, journals and letters touching on his life as an artist, which this Museum acquired in 2004

![]() Essai de reconstitution (Trois tiroirs)

Essai de reconstitution (Trois tiroirs)

Attempt at Recreation (Three Drawers)], 1970-1971

Formerly Trois Tiroirs (Three Drawers).

A tin-plate chest containing three drawers held shut with wire netting, each

sporting a label and containing various objects.![]()

This three-drawer tin-plate chest epitomises Boltanski’s early ventures

into the theme of lost child hood.

He wrote his first book, “Recherche et présentation de tout ce qui reste

de mon enfance, 1944-1950” (Investigation

and presen tation of all that is left of my childhood, 1944-1950) (1) in 1969.

He originally only published 50 copies of this book which was, in a way, an

attempt to recreat e a period of his childhood and present the result as a work

of art. Its nine p ages contain a school photo and essay, and keepsakes that

remind us of the bits and pieces we might have stored away caringly in cardboard

boxes.

Trois tiroirs is a similar – but more three-dimensional recreation. The drawers contain plasticine objects replicating things which, as the typed labels on each drawer tell us, Boltanski probably had as a child (planes, a hot-water bottle and so on). They are his way of reminding us of those inconsequential treasures we prized and cherished as children.

This recreation also captures something of the earnest seriousness that childhood games somehow involve, making it both funny and endearing.

It also foreshadows a series of archive works that Boltanski produced in the 1980s (2). Those, again, feature the same tin-plate chests full of unpretentious, commercially worthless objects encapsulating an undeniably huge wealth of private emotion-steeped memories.

- (1) See reference text below

- (2) See Les archives de C.B. 1965-1988 below

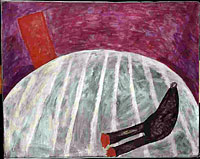

![]() Vitrine de référence (Vitrine of Reference), 1971

Vitrine de référence (Vitrine of Reference), 1971

A painted wooden box under Plexiglas, containing photos, hair, fragments of the artist’s clothes, a sample of his handwriting, a page of his reading book, 14 earth balls in a pile, a trap consisting of three objects made of pieces of cloth, wire, pins. Wood, Plexiglas, photos, hair, fabric, paper, earth, wire. 59.6 x 120 x 12.4 cm. ![]()

This piece takes us a step further down Boltanski’s ventures into his own life and past. He made several of these showcases to display personal belongings staging them as relics or as archaeological vestiges of lost civilisations.

They are also his way of caricaturing the Musée de l'Homme, the anthropological museum in Paris. Boltanski himself explains what had struck him there. The artefacts lying under dusty glass windows had been manufactured with no aesthetic purpose to start with. Now that the museum had also sapped the value they once had as practical implements, they had become something more akin to documents than to works. He went on to describe muse ums as “devoid of reality, worlds unto themselves, protected, where everything is supposed to look nice.” Museums, in other words, are in a time warp of their own. They are not real. Or unreal. And they convey that bizarre status to the relics they contain.

So presenting some of his own personal belongings in a museum-like showcase was Boltanski’s way of keeping his own relics. And of mummifying them.

![]() Saynètes comiques (Comic Vignettes), 1974

Saynètes comiques (Comic Vignettes), 1974

Le mariage des parents (Parents’ wedding)

Photograph. Three silver proofs, assembled alongside text written with white

ink on blue cardboard.

37.9 x 71 cm. Each photo measures 28.5 x 18.3 cm.![]()

1974 saw Boltanski’s autobiography-exploring endeavours take a lighter

turn. Or, as he put it in his memoirs, “he outdid himself, he surpassed himself,

he took a step back and started making fun of himself. He stopped talking about

his childhood a nd started playing with it” that year.

He actually seems to shy away from the solemnity that shrouded his

previous endeavours. Until then, he had been trying to tell the story of Christian

Boltanski the character. But then he got to a point where, in his words, “That

make-believe character became too heavy, and I felt the urge to kill it (…)

kill the myth (…) kill it in ridicule.” (Boltanski, in an interview with Delphine

Renard published in the Centre Pompidou catalogue in 1984).

Hence the Saynètes Comiques, a series of 25 pieces containing photographs

he had touched up using pencils or pastels. Again, they recount his life, but

they do it farcically this time.

Each photograph or group of mounted snapshots shows a family milestone (a funeral, wedding or birthday), which he had re-enacted for the camera. So all the characters are actually Boltanski disguised in a few accessories. That gives these images an unpretentious, almost scruffy look and street-theatre atmosphere that ultimately elicits contempt. The backdrops are often drawn in, adding to the spaghetti-western feel, and some of the labels explaining the scenes exacerbate the grotesque ingredient.

![]() Composition théâtrale (Theatrical Composition), 1981

Composition théâtrale (Theatrical Composition), 1981

Cibachrome in a black showcase frame. 241 x 124.5 x 8.8 cm.

Detail of a triptych: 241 x 373.5 cm.![]()

Boltanski was using photography extensively in the late 1960s. At first,

he took small black-and-white phot os from family albums or photos that otherwise

had some documentary value, and displayed them alongside text or other items.

Then he started using this technique in a completely different way in the mid

1970s. He started showing large colour photos with no accompanying text or items

(thus carrying the message single-handedly). He created a series he called Compositions.

Depending on the object they portrayed, they were heroic, grotesque, architectural, Japanese or enchanted. The photographs

were invariably huge and the backgrounds invariably jet black, making the tiny

objects they depicted look monumental. There is something in their overblown

size and colour contrast that makes them look like a vision. The black background

makes the figures stand out like shadow puppets in the light. It also nestles

them in an unfathomable void, isolating them in a sort of endless realm.

His 1981 Compositions Théâtrales feature diminutive corrugated-cardboard

puppets that he had made for the occasion with wire and paper fasteners. These

clever little makeshift characters are unmistakably reminiscent of the corrugated-cardboard

objects that Picasso used in the 19 10s, with the difference that Boltanski

made these toys for himself. They belong to Boltanski’s private, nearest-and-dearest

treasure chest. He speaks of them as voodoo fetishes, explaining that they are

made of tatty scraps yet harbour enormous evocative power. The public only sees

them in the photographs that make them look huge and beyond reach. Boltanski,

incidentally, spoke of photography as the “cooling off’ or separation

stage. And, in a 1984 interview, explained that “objects are in the intimate,

touchable realm: photographs in the realm of representation” (Boltanski,

exhibition catalogue, Centre Pompidou). Photographs, in other words, have a

way of transfiguring manual work.

![]() Les archives de C.B. (C. Boltanski Archives), 1965-1988, 1989

Les archives de C.B. (C. Boltanski Archives), 1965-1988, 1989

Installation with light.

Metal, photographs, lamps, electric wire. 270 x 693 x 35.5 cm.![]()

Les archives de C.B. 1965-1988 shows Boltanski back in touch with the high call he had defined thus in 1969: “To keep traces of every insta nt of our life, of all the objects that have come into contact with us, of everything we have said and everything that has been said around us: that is my goal”.

For this project, he built a wall using 646 tinplate biscuit tins,

covered in varying degrees of rust, mirroring passing time’s corroding force.

He had used tins like these back in 1970, when he was working on his Trois

Tiroirs, for example, to house plasticine replicas of toys from his childhood

(1).

But Les archives de C.B. 1965-1988 is on a different scale altogether. The

646 tins are stacked nearly three metres high, lit by black desktop lamps and

amid dangling electric wires. The impression is that the whole piece was erected

in a rush. The implication is that this is a makeshift archive, thrown together

to rescue things otherwise doomed to oblivion.

These tins contain more than 1,200 photos and 800 documents that Boltanski gathered

when he cleared his atelier. These tins, in other words, contain records from his entire life as an artist, shielded from view. They are only present in

his memory and privacy.

Boltanski ventured back to this personal-archive theme in 2001 with La Vie impossible

(The Impossible Life), a string of 20 display cases crammed with all sorts of

papers. Again, if this time he did not hide his keepsakes from sight, he stashed

them in such a mess that their mystery remains unfathomed .

(1) See above.

![]() Réserve (Reserve), 1990

Réserve (Reserve), 1990

Installation.

Fabric, lamps. Variable dimensions.

Purchased in 2000.![]()

Boltanski started using a new raw material, clothes, in 1988. They first appeared in a poignant piece, Réserve, Canada. This work echoes the warehouses that Nazis used to store the belongings of the deported. Boltanski, in other words, associated clothes with death from the outset (as he had with photography). In his words, “Someone’s photograph, garment or dead body are pretty much the same thing: there was someone there, now they’re gone.” Garments are also vestiges or marks that bear testimony to a life now past.

That is what clothes meant in the string of Réserves that followed. They are all installations that play on the subject of death and memory. In his 1989 Réserve: la Fête de Pourim (Purim Holiday) and 1990 Réserve: Lac des morts (Lake of the Dead), the clothes lay on the floor. In his 1989 Réserve du Musée des enfants (Children’s Museum), he stacked them in rows (1).

For his 1990 Réserve, he lined the walls of a whole room in loft-smelling

hand-me-down clothes. Because this work’s overbearing presence is not just

visual: it is also olfactory – a dimension that plastic art does not

use enough (2).

Much like the other works in this series, the atmosphere that the 1990 Réserve

creates is a door to melancholic contemplation of the body as a brittle vessel,

vanity and death (all of which ranked among Boltanski’s favourite themes in

the 1990s).

- (1) This work can be seen at the Dernières Années (Last

Years) exhibit ion at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art ![]()

- (2) One of the works in the collections of the Musée national d'art moderne

that best explored this dimension before Boltanski’s Réserve is Beuys’ Plight, 1985 (see the Online collection, Numéro d'inventaire : AM 1989-545).

timeline

1958

Boltanski’s first paintings. They were figurative in style. He switched

from painting to more experiment al media in 1967.

1966

Met Jean Le Gac. They teamed up in 1969 and worked together for a few years

after that.

1968

Staged his first personal exhibition, in the Théâtre du Ranelagh ( Paris),

featuring life-size but deliber ately rudimentary puppets and a film that arguably

condensed what his early work was all about: La Vie Impossible de Christian Boltanski.

1969

Published his first book, Recherche et présentation de tout ce qui reste

de mon enfance, 1944-1950, heralding the autobiographical element in his work

.

1970

Started working on his Vitrines de Référence series. This project stretched

into 1973.

1972

First exhibition in Documenta 5, Kassel (), in the “Individual Mythologies” section.

1975

After one last light-hearted d ig at his autobiography in his 1974 Saynètes

Comiques series, he chucked his own character and moved on to explore cultural

codes and clichés (ad portraits or honeymoons in Venice, for instance). He used

colour photographs – blowing them up to increasingly overbearing dimensions

– to do so.

1977

Started working on his Compositions, with huge painting-size photographs.

1984

Retrospective at the Musée national d'art moderne. An opportunity for him

to experiment with a new way of displaying his work. This exhibition was split

into two sections: one was autobiographical (showcasing his documents and archives)

and the other photographic (with large photographs more akin to classic pictorial

works).

1985

Started working on the Monuments series. The subjects, here, were photographs

of nameless faces on walls in altar-like constructions or constellations lit

by small lamps.

1986

Was invited to the Venice Biennale and took over an area in an old prison,

Palazzo delle Prigione, to house his exhibition in half light (which became

a constant feature in subsequent exhibitions).

1987

Broached the Holocaust for Documenta 8

in Kassel. He had done so before, but never so bluntly.

1988

Clothes appear in his work.

1990

Started his Les Suisses morts (The Dead Swiss) series, using photographs

from a Swiss newspaper’s obituaries. He chose the Swiss because, in his words,

they “have no reason – or at least historical reason – to die”. This work shows

Boltanski’s thoughts turning to the brutality of death in general.

1998

Dernières Années exhibition at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art. This

show was designed as a single walk-through piece. It features the issues Boltanski

has been broaching of late (how presence and absence intermingle in memory,

in particular).

2003

Entre-temps (Meanwhile) exhibition at the Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris.

Boltanski picks up the autobiographical theme again.

2004

The Museum of Jewish Art and History ran a year-long exhibition for his Théâtre

d'ombres (Shadow Play).

REFERENCES / BIBLIOGRAPHY ![]()

For references and bibliography : you can consult the French version of the file Boltanski.

To consult the other dossiers on the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

Contacts

So that we can provide a service that meets with your requirements, we would like to have your reactions and suggestions regarding this document.

Contact: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

Text : Vanessa Morisset

Layout : Michel Fernandez / Ariane Cock-Vassiliou

Translated by Vice Versa

Copyreader : Olivier Rosenthal

Dossier on-line at www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ section on ‘Educational

Dossiers’

Co-ordination: Marie-José Rodriguez