A Movement, A Period

![]() Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

A Movement, A Period

|

|

|

|

|

Georges Braque, Le Viaduc à L’Estaque (The Viaduct at L'Estaque), 1908 - © Adagp, Paris 2007 Attention ! The Internet copyrights of this work only have been obtained in the frame of this file dedicated to the Cubism. |

The Artists and their Works

Georges Braque

• Le Viaduc à L'Estaque, 1908

• Les Usines du Rio-Tinto à L'Estaque,

1910

• Compotier et cartes, 1913

Pablo Picasso

• Le guitariste, 1910

Juan Gris

• Le livre, 1911

• Le petit déjeuner, 1915

Fernand Léger

• La couseuse, 1909-10

• La noce, 1911

• Contrastes de formes, 1913

Albert Gleizes

• Paysage à Toul, 1915

Raymond Duchamp-Villon

• Le Cheval majeur, 1914-1976

Henri Laurens

• Bouteille et verre, 1918

Cubism is without a doubt the most highly influential movement in the history of modern art. A descendant of Cézanne’s research on the creation of a pictorial space that is no longer a mere imitation of reality, and ‘primitive’ art that challenges the obvious of Western tradition, Cubism disrupts the notion of representation in art. According to art historian John Golding, who specialises in the movement, Cubism is an absolutely original pictorial language, a totally new approach to the world, and a conceptualised aesthetic theory. So one can understand how it was able to give new direction to all of modern art.

Through several phases of exploration, the protagonists of the movement initially examined the unity of the canvas and the treatment of two-dimensional volumes. This was the first phase of Cubism, known as Facet or Cézanne Cubism, from 1908 to 1910. Once the painting had gained autonomy, the issue of space became clearer, evolving into a kind of deconstruction of the perceptive process. Thus, the movement’s development from 1910 to 1912 is often referred to as Analytical Cubism. After verging on abstraction and hermetism, the artists reintroduced readable signs, particularly by introducing everyday objects, newspaper and papier collé to the canvas, steering Cubism towards an aesthetic reflection on the different levels of reference to reality. This final stage was referred to as Synthetic Cubism.

The first two phases were led by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, neighbours at the Bateau-Lavoir complex of artists’ studios in Montmartre who worked closely together. They were then joined by Juan Gris, who began painting in the Cubist style in 1911, and sculptor Henri Laurens in 1915 who further developed their research.

But Cubism also influenced the young generation of artists in the nineteen tens, whose first artworks portrayed their interpretation of the movement’s contributions. Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger, Albert Gleizes, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp) were given an impetus that led them to great discoveries.

The influence of Cubism was felt throughout Europe, spilling over into both ready-mades (1) and abstract art (2). Piet Mondrian’s abstract artwork, Russian Constructivism, Kasimir Malevitch’s Suprematism, and even Futurism, which would rival Cubism, are all indebted to the innovations first established by Braque and Picasso.

--> (1) Consult the file : Marcel Duchamp (en)/ L'oeuvre de Marcel Duchamp (fr)

--> (2) Consult the file : La naissance de l’art abstrait

The artworks selected for this dossier on Cubism are based on the Museum Collection files that are already on line. Consult the dossiers listed for additional information.

Georges Braque

Argenteuil (Val-d'Oise), 1882 – Paris, 1963

![]() Georges Braque, Le Viaduc à L'Estaque,

(The Viaduct at L'Estaque), 1908, Paris

Georges Braque, Le Viaduc à L'Estaque,

(The Viaduct at L'Estaque), 1908, Paris

Oil on canvas, 72.5 x 59 cm,

Payment in kind, 1984

AM 1984-353

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Attention ! The Internet copyrights of this work only have been obtained in the frame of this file dedicated to the Cubism.

The little fishing harbour of L’Estaque near Marseilles drew a number of artists in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Cézanne sought refuge there during the war of 1870 and then returned to sojourn on several occasions. Braque followed in his footsteps, heading there for the first time in 1906, and then again in 1908 after having seen a major posthumous retrospective on the Aixois painter at the Salon d’Automne. During an interview, he confided that he went there “with a pre-conceived idea… my first paintings of L’Estaque were already in my mind before my departure”.

Among the artworks created during his second stay in the summer of 1908, Le Viaduc à L’Estaque bears witness to the homage to Cézanne from which Braque developed his own painting style.

In this painting, a concern for constructing a space specific to the canvas, and not bound to a faithful imitation of reality, drove the artist to eliminate details, to simplify the shapes of houses and reduce them to cubes. Braque had no doubt read the famous passage of Cézanne’s correspondence with Emile Bernard, published in 1907: “Let me repeat what I told you here: deal with nature as cylinders, spheres and cones”.

Braque took Cézanne’s invitation to represent shapes geometrically as an agenda. Exhibited among others of the same series the following autumn in Paris, this painting caused art critic Louis Vauxcelles to echo one of Matisse’s witticisms and describe Braque’s artwork as being composed of “little cubes”, thereby inaugurating a new style he coined “Cubism”.

![]() Georges Braque, Les Usines du Rio-Tinto à L'Estaque,

automne 1910

Georges Braque, Les Usines du Rio-Tinto à L'Estaque,

automne 1910

Oil on canevas, 65 x 54 cm

Gift from Mr. and Mrs. André Lefèvre, 1952

AM 3973 P

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Attention ! The Internet copyrights of this work only have been obtained in the frame of this file dedicated to the Cubism.

Also painted at L’Estaque, this artwork holds almost nothing of a singular landscape. The location is no longer recognisable, the image strays from the motif. It could have been painted anywhere. As of 1909, Braque ceased working outside, turning away from picturesque circumstance to become, like Picasso at the time, increasingly interested in the construction of a unified, homogenous space proper to the painting.

“What really drew me – and this was the main direction of Cubism – ”, said Braque to art historian Dora Vallier, “was the materialisation of this new space I could feel. (…) The first Cubist painting was all about the search for space. As for colour, the light was all that interested us. Light and space are two things that are connected (…). I used fragmentation to establish space and the movement of the space and I could only introduce the object once I had created the space. (…) For Fauves, it was about light, for Cubists it was space.”

In Les Usines du Rio Tinto, Braque renounces the immediate, apparently natural and automatic, perception of space that perspective reproduces. Using this familiar landscape as a starting point, he works on the intellectual reconstruction at play in perception: forming a single image from a multiplicity of small perceptions grasped by the body in movement. The painting becomes a tool for analysing the perception of reality, whence the term Analytical Cubism for the artworks of this period.

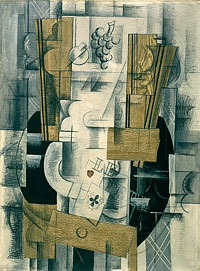

![]() Georges Braque, Compotier et cartes (Fruit Dish and Cards)

, début 1913, Paris

Georges Braque, Compotier et cartes (Fruit Dish and Cards)

, début 1913, Paris

Former title: Composition de l’As de Trèfle, Nature morte aux cartons à jouer, Nature morte au jeu de cartes, Les deux cartes à jouer

Oil, heightened with pencil and charcoal on canvas, 81 x 60 cm

Donation from Paul Rosenberg, 1947

AM 2701 P

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Attention ! The Internet copyrights of this work only have been obtained in the frame of this file dedicated to the Cubism.

By 1911-1912, Braque and Picasso understood that their painting had become less and less readable, bordering on abstraction.

That is the path that artists such as Robert Delaunay (1) would take, while the pioneers refocused their work on the issue of painting’s connection with reality. They reintroduced signs so that comparisons could be made between the space of the representation and reality.

In 1912, they even started to incorporate elements taken directly from reality. By introducing, for example, a piece of oilcloth in Nature morte à la chaise cannée (Still Life with Chair-Caning), Picasso uses this trompe-l’œil to mean that the artist is not a slave to reproducing reality (2).

In Compotier et cartes, Braque takes this a step further. He draws a cluster of grapes that evokes classic representation; he then adds a few playing cards to emphasise the Cubist practice of cutting up reality into volumeless facets, and paints – not “faux wood” – but rather faux “faux wood”. In other artworks, he imitates wood, or glues wallpaper as “faux wood”. Here, he oversteps another boundary by imitating paper that imitates wood. Cubism thus results in a sophisticated reflection on the different possible levels of reference to reality.

--> (1) See the file : Futurisme, Rayonnisme, Orphisme. Les avant-gardes avant 1914

Biography

George Braque’s father, an artisan decorator in Argenteuil, taught him the techniques of trompe-l’œil, faux wood and faux marble, which were decisive elements in Cubist preoccupations.

He studied painting at the Académie Humbert in Paris. After discovering the Fauves at the Salon des Indépendants in 1905, he embarked upon avant-garde work that brought him into the circles of the young Parisian painters. That was how, in 1907, he found himself in Picasso’s studio during the creation of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Inspired by the canvas, Braque painted his large Baigneuse (Bather), finished in 1908, which marked a turning point and lay the foundation for Cubism: the figure is deformed, beiges and greys make their appearance, the background is comprised of sections of angular cut-outs. Much less violent than Picasso’s Demoiselles, this canvas triggered the complex pictorial exploration that would occupy Braque and Picasso in the years to come.

1908 was also the year of his first solo exhibition. The Kahnweiler gallery in Paris displayed a series of paintings done during the summer at L’Estaque, particularly Le Viaduc à L’Estaque. The canvases, dubbed “Cubist” by critic Louis Vauxcelles, set out the problematics of space based on the legacy of Cézanne. Until 1910, Braque worked in close collaboration with Picasso, which brought their artwork to the threshold of abstraction. Then, in 1911, he began reintroducing more readable elements, first letters, then papier collé, then trompe-l’œil techniques.

His Cubist adventure with Picasso came to an end in 1914, when Braque was called to war. Upon his return, he drew closer to Gris and began what was like a second career, deriving conclusions from Cubism, without limiting himself to them. In the twenties, he reintroduced colour to his still lifes, while pursuing his reflection on space and the inbetweenness that connects objects.

In 1948, he was awarded first prize for painting at the Venice Biennale.

Malaga, 1881 – Mougins, 1973

![]() Picasso, Le Guitariste (The Guitarist),

summer 1910

Picasso, Le Guitariste (The Guitarist),

summer 1910

Assigned title: Le joueur de guitare (The Guitar Player)

Oil on canvas, 100 x 73 cm

Gift from Mr and Mrs André Lefèvre, 1952

AM 3970 P

© Succession Picasso, Paris 2007

Painted during the summer of 1910 while Picasso was on holiday at Cadaques, this canvas, as though drenched by the Catalonian sun, uses distinctively Cubist means to evoke the staccato rhythms of music. Conjuring up the sound of frenzied guitar playing, the lines that articulate the canvas transform it into an artwork that moves away from figuration to become an almost abstract image.

The facets that broke up the volumes in Picasso’s previous works are fewer in number and pared down in shape. They no longer appear as an outcome of decomposition, but assert themselves and structure the canvas with a vigorous architecture of lines and angles.

That said, some elements help clearly identify the guitarist figure. His head perched on the cylinder, at the top of the painting, his shoulders, his arms, right down to the neck of the guitar at the centre, all these clues attest the fact that Picasso, just like Braque, refused to create a painting with no connection to reality. In his later works, Picasso would invent all kinds of signs that, each in their own way, made reference to reality.

--> For others works of the painter in the cubism period, see the file : Pablo Picasso (en)

or Pablo Picasso (fr)

Biography

Of Andalusian origin, Pablo Ruiz Picasso grew up in the South of Spain and was taught drawing and painting at an early age by his father, who was himself a painter.

A brilliant student at the Fine Arts Academy in Barcelona, he moved to Paris in 1904 where he struck up friendships with poets Max Jacob and Pierre Mac Orlan, and above all with a man who would play a central role in the history of Cubism, Guillaume Apollinaire.

He also met Matisse, who introduced him to Negro art. This statuary art, blended with forms from Iberian and Catalan painting, sparked his in-depth reflection on the manner of rendering volume.To shed some light on these issues, motivated by the Cézanne retrospective of 1907, Picasso started to create the painting that founded all modern art, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Although, from a certain point of view, this painting is in the continuity of nude iconography, particularly following the bather theme of Ingres and Cézanne, it nevertheless makes a radical break from painting as imitation. Even though, as John Golding points out, Les Demoiselles is not, strictly speaking, a Cubist painting, since Cubism is a form of realism, and insofar as it is a detached, objective reinterpretation of the outside world, a classic art form, Picasso’s painting is nevertheless the logical starting point for the history of Cubism.

After this painting, Picasso and Braque embarked upon an adventure. Together, they moved Cubism from the Cézanne phase to an analytical period of extreme exploration, before coming back to more readable creations with Synthetic Cubism.

The outbreak of war brought an end to their collaboration. Since Picasso was of Spanish nationality, he was not called to war. Braque, on the other hand, had to join his regiment, as did Derain, Léger and even Apollinaire.

Picasso’s wartime research brought about a radical change in style, focusing once again on classic figuration. This new direction was unveiled to the public on the drop curtain of the ballet Parade in 1917. Much later, in the fifties, Picasso fully renewed with Cubism with the creation of his cut metal sculptures.

Madrid, 1887 – Boulogne-Billancourt (Hauts-de-Seine), 1927

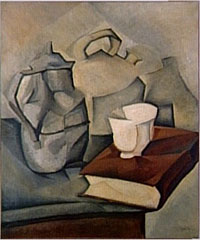

![]() Juan Gris, Le livre (The book),

1911

Juan Gris, Le livre (The book),

1911

Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm

Gift from Louise and Michel Leiris, 1984

AM 1984-518

© Public domain

This small painting is one of Gris’ first steps towards Cubism, in which he methodologically studies various volumes, as though he were taking up painting from the beginning or, more precisely, what constitutes a beginning for Cubism, Cézanne’s teachings.

Gris drew on Cézanne’s theme of a modest still life, seen from a slightly higher vantage point, and thus playing with the different planes that form the background of the painting. But like his Cubist companions, here Gris separates the issues surrounding mise en espace from other profoundly Cézannian concerns, such as the constituent power of colour.

Gris’ still life is in fact constructed in monochrome, as though colour had to wait until the study of volume was far enough advanced before it could be taken into consideration again. Gris would not hesitate to reintroduce it once he had found his own Cubist style. As early as 1912, for example, in Le Portrait de Picasso, blue takes hold of the facets that represent his friend’s jacket.

--> To see Le Portrait de Pablo Picasso, 1912, The Art Institute of Chicago

![]() Juan Gris, Le petit déjeuner (the breakfirst),

1915

Juan Gris, Le petit déjeuner (the breakfirst),

1915

Oil and charcoal on canvas, 92 x 73 cm

Purchase, 1947

AM 2678 P

© Public domain

When the war broke out, Juan Gris took refuge at Collioure (France) with Matisse, and his contact with the artist is undoubtedly what helped him fully rediscover the sensual side to painting through the effects of colour.

Ultramarine blue invades the painting through the open window, letting in the air from outside, and forms a stark contrast with the usual confined spaces of Cubism. This bright, fresh blue illuminates the faux red wood and the green rug in the dining room.

In such a way, the morning still life with the bowl, the coffeepot, the coffee mill and the newspaper expresses vitality and great readability. Even though the image is composed of cut-outs, superimpositions, folded planes and fragmented objects, it seems simple and infused with a dynamic quality. Thanks to Gris, Cubism renewed with praise for life.

Biography

A native of Madrid, Juan Gris arrived in Paris in 1907, where he used his background as an illustrator to make ends meet. He set up in a studio at the Bateau-Lavoir complex, near Braque and his fellow countryman, Picasso. He followed the development of their work right from 1907, but did not immediately paint in the Cubist style himself. His first artworks were Art Deco gouaches, and then more naturalist paintings.

Gris adopted the Cubist style in 1911, but without taking the methods to such an extreme conclusion. He plunged back into the study of Cézanne, methodically returning to the basics of Cubism. In particular, Gris carried on with the high vantage points so dear to Cézanne.

But this return to Cézanne was done through the previously established Cubist preoccupations. Gris renewed with Cézanne to answer what were already highly elaborate questions, such as the treatment of space between objects.However, this return to the roots was not Gris’ only contribution to the movement. As an illustrator, he grew accustomed to simplifying shapes and producing clearly readable drawings. Under the influence of Matisse, he reintroduced sparkling colours that restored the painting’s sensual side. In such a way, he gave Cubism a clarity and serenity that made it easier for the public to understand.

Gris remained true to his focus on the object in space until his death at the early age of 40.

Argentan (orne), 1881 – Gif-sur-Yvette (Essonne), 1955

![]() Fernand Léger, La couseuse (The Sewer),

1909-1910

Fernand Léger, La couseuse (The Sewer),

1909-1910

Assigned title: La Mère de l’artiste (The Artist’s Mother)

Oil on canvas, 73 x 54 cm

Gift from Louise and Michel Leiris, 1984

AM 1984-578

© Adagp, Paris 2007

This painting shows the founding role Cubism played in Fernand Léger’s work. Indeed, for an entire generation of artists, Cubism served as a base from which to reinvent painting. Here, Léger follows Cézanne’s advice and treats the figure in a geometric manner. He attempts an intimist subject, since the model is his mother.

But contrary to Cézanne, he abandons colour and creates a painting in the grey beige tones typical of Cubism. This work taught him how to control volume, which he treated more like a mass of fragments, as opposed to the tubes found on a number of occasions in his later work.

![]() Fernand Léger, La noce (The Wedding),

1911

Fernand Léger, La noce (The Wedding),

1911

Former title: Les Noces, Composition aux personnages

Oil on canvas, 257 x 206 cm

Donated by Alfred Flechtheim, 1937

AM 2146 P

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Created in 1911, La Noce reveals a change in direction in the artist’s work, and in his focus, similar to that of the young Puteaux painters he kept company with. In his large-scale paintings – contrary to the intimist still lifes of Braque, Picasso and Gris during the same period -, colour makes a comeback, perhaps as an influence of Delaunay.

Léger’s wedding theme requires a number of characters and, by its very nature, calls for a monumental approach. On either side of a large, central, white wave that evokes the bridal gown, a procession of figures are jumbled together, overlapping one another. A hand, an arm, a hat emerge from the hotchpotch here and there. Snatches of landscape are visible on the sides, as though relegated there by the surging crowd.

Between the planes that structure the pictorial surface, only a

few trees and houses recall the Cubism of Braque and Picasso. In this

painting, the tumult that characterised Fernand Léger’s work until

the early twenties was already well established.

![]() Fernand Léger, Contrastes de formes (Contrasts

of Forms), 1913

Fernand Léger, Contrastes de formes (Contrasts

of Forms), 1913

Oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm

Gift from Mr and Mrs André Lefèvre, 1952

AM 3304 P

© Adagp, Paris 2007

As of 1912, the Cubist fragmentation of forms in Léger’s work transformed into a systematic search for opposition of pictorial elements, in an effort to make a distinctive dynamic spring forth from the painting.

This exploration produced a series of artworks entitled “Contrasts of Forms” (some have a specific title, such as Le Réveille matin, 1914), an abridged version of “contrasts of forms and colours”, covering an “opposition of values, lines and opposite colours

In this 1913 painting, there is at once an opposition of straight and curved lines, an opposition of shapes between cones and cylinders, an opposition of primary colours amongst themselves and, lastly, an opposition of values among black, white and colours.

Far from being merely formal research, Contrastes de formes allowed Léger to take up a theme he would always hold dear. He wanted to use these compositions to attain a visual intensity equivalent to the intensity of life, which explains the purposefully rushed look to these paintings.

But although Léger produced abstract art with Contrastes de formes, he would not continue down this path. His search for pictorial intensity would then renew with figuration and exalt more precisely modern life.

Biography

After studying architecture at Caen between 1897 and 1899, Fernand Léger learned painting in Paris, at the Académie Julian in particular. During this time, he also worked at an architect’s office and retouching photographs for a photographer, two fields that would leave a lasting mark on his artwork.

He painted in the Impressionist style until the Cézanne retrospective of 1907, which led him to explore the rendering of volume. Around 1909, he set up at La Ruche studio complex in the Montparnasse quarter, where he met avant-garde painters like Robert Delaunay and Marc Chagall, and poets like Max Jacob. He discovered the Cubism of Braque and Picasso through Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, but was drawn more to the Duchamp brothers and the Puteaux group.

His first solo exhibition took place at the Kahnweiler gallery in Paris in 1912. By 1913, his painting was already moving towards abstraction through the theory of contrasts he shared with Delaunay.

Even though he was conscripted in 1914, he continued to paint. Upon his return from war in 1917, colour invaded his paintings that celebrated technique and modern life. Le Cirque (1918) and Les Disques dans la ville (1920) bear witness to his infatuation with machines and his trust in man, two omnipresent themes in his work.

Paris, 1881 – Avignon (Vaucluse), 1953

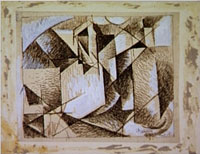

![]() Albert Gleizes, Paysage à Toul (Landscape at Toul),

1915

Albert Gleizes, Paysage à Toul (Landscape at Toul),

1915

Brown ink, heightened with white gouache on paper

12.8 x 26 cm

S.D.T.B.DR.: AlbGleizes/Toul-15

Gift from Mr and Mrs Livengood, 1954

AM 1890 D

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Gleizes created this drawing when he was conscripted in Lorraine, at Toul. His difficult living conditions did not hamper his production. Rather, they drove him to create sketches in which his painting is simplified to abstraction. In Paysage à Toul, which conveys the architecture of a bridge over the Moselle River, he imposes upon Cubism a demand for pure geometric shapes.

In this investigation, bringing space into play does not conflict with perspective. There is even an illusion of volume, which Gleizes promotes in his writings. There is in fact a suggestion of three dimensions through the arrangement of the different planes. The way he treats space is not controversial as with Braque and Picasso, who renounced the conventions of perspective. Gleizes brings us Cubism turned classic.

Biography

Paris-born Albert Gleizes first learned the decoration trade from his father, who had a small studio. A self-taught painter inspired by Impressionism, he exhibited his artworks in 1903 and 1904 at the Salon d’Automne. In 1906, he founded a utopian community of artists and writers in Créteil who explored themes of modernity following the guild revival in England.

He discovered nascent Cubism through young painters like Jean Metzinger and Robert Delaunay, who he met around 1908, and who contributed to the development of his painting in increasingly geometric shapes. He then encountered Fernand Léger, who had a very similar style: he painted a few large canvases with tubular figures. He did not make acquaintance with Picasso until 1911. In 1912, he and Metzinger published Du Cubisme, the first theoretical work on the movement, and he was one of the artists behind the Section d’Or, a major Cubist exhibition at the Galerie La Boétie in Paris.

Called to service when the war broke out, he spent a year at Toul. He was then discharged and thus able to leave France for New York, where he met up with Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, who he had known since the founding of the Section d’Or.

When he returned to Paris after the war, he presented his works at several exhibitions. In 1926, he retired to Isère, where he founded a community of religious painters and artisans.

Damville (Eure), 1876 – Cannes (Alpes-maritimes), 1918

![]() Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Le Cheval majeur (The

Great Horse), 1914-1976

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Le Cheval majeur (The

Great Horse), 1914-1976

Sculpture. Bronze with black patina, 150 x 97 x 153 cm

Cast by: Susse fondeur Paris

S. D. DED. on the back of the base: R. DUCHAMP-VILLON / 1914 / EPREUVE DU MUSEE

NATIONAL D'ART MODERNE / Susse fondeur Paris

Purchase, 1976

AM 1977-206

© Public domain

This sculpture, created following a number of sketches that pared down its shape, represents a hybrid between the horse and the machine, between the biological and the mechanical. The animal’s silhouette is composed of alternating rounded shapes and more rectilinear parts reminiscent of rods and pistons. The sculpture could be considered an illustration of the expression “horsepower”.

In such a way, Duchamp-Villon praises the power of the horse in a manner akin to Futurism, an aggressive artistic movement that exalted the machine (1). In 1913, the work of Futurist painter and sculptor Boccioni was presented in Paris, which may have had an influence on Duchamp-Villon, just as it influenced his brother Marcel for the representation of movement in Nu descendant l’escalier and Le jeune homme triste dans un train (2).

This sculpture thus sets off a fusion between vitality and mechanical power, at the same time as a fusion between the two main avant-garde movements of the nineteen tens.

--> (1) See the file : Futurisme, Rayonnisme, Orphisme. Les avant-gardes avant 1914

--> (2) See the file : (1) Consult the file : Marcel Duchamp (en)/ L'oeuvre de Marcel Duchamp (fr)

Biography

Born at Damville near Rouen (France), Raymond Duchamp-Villon was brother to Jacques Villon and Marcel Duchamp, with whom he worked closely in the beginning. He gave himself over to sculpture after a long illness that forced him to cease his studies in medicine.

He was quick to exhibit at the Salon d’Automne in 1905, but until the beginning of the nineteen tens, his artworks remained rather conventional, following in the wake of Rodin’s exploration of the fragmented body.

Then, with artworks like Baudelaire, and Maggy in 1911, he produced more massive volumes that conveyed great power. That same year, he and his brothers created the Section d’Or group in Puteaux, which soon grew to include Robert Delaunay, Fernand Léger and Albert Gleizes. Their group formed the second generation of Cubist artists.

Before being called to service for the war, he created his most famous piece, Le Cheval majeur, which remained in its original plaster state and was not cast in bronze until much later. Stricken by typhoid fever, he died in 1918.

Paris, 1885 - Paris, 1954

![]() Henri Laurens, Bouteille

et verre (Bottle and Glass), 1918

Henri Laurens, Bouteille

et verre (Bottle and Glass), 1918

Assemblage

Polychromed wood and sheet iron, 62 x 34 x 21 cm

Gift from Louise and Michel Leiris, 1984

AM 1984-569

© Adagp, Paris 2007

Attention ! The Internet copyrights of this work only have been obtained in the frame of this file dedicated to the Cubism.

Henri Laurens pursued the initial exploration on volume by Braque and especially Picasso, carrying on with the themes and materials they invented, such as the treatment of the transparency and reflection of glass with opaque materials (see Picasso’s 1914 Verres d’absinthe series).

Like Picasso, Laurens worked on the effects of intersecting planes that give shape to the main lines of the bottle and its reflections. He diversified his materials, using wood and sheet metal to create tactile variations. And, above all, he insisted upon diversity of colour, which he felt provided the sculpture with its own light.

But, unlike Picasso, he did not work with found materials or scrap. His treatment of volume broke with the spontaneity of the first Cubist sculptures to offer a more structured art of assemblage, one that paved the way for other movements like the Constructivism of Gabo and Pevsner.

Biography

A native of Paris, Henri Laurens was first trained in ornamental structure and practised traditional stone carving directly on building sites, a technique he would return to in the twenties. Likewise, he retained an interest in medieval, roman and gothic sculpture.

Alongside this work, he took drawing lessons and created sculptures in the manner of Rodin. He thus approached Cubism as a sculptor, unlike Braque and Picasso who dealt with volume in an experimental way. He settled in the Montmartre quarter, where he worked in isolation for a few years before meeting Léger in 1909 during a stay at La Ruche studio complex. In 1911, he met Braque who would become a close friend.

His first Cubist works, however, did not appear until 1915, demonstrating great maturation and great insight into the contribution of Cubism to the history of sculpture. Due to a disability, he was not called to service during the war and was able to pursue his artistic career.

He took a Cubist attitude to his work until 1925, and then renewed with stone and monumental sculpture in the round.

1907

- A major Paul Cézanne retrospective is held at

the Salon d’Automne in conjunction with the publication of the artist’s

correspondence with his friend, Emile Bernard.

- Picasso paints Les Demoiselles d’Avignon at

his Bateau-Lavoir studio in Montmartre.

- Georges Braque visits him and discovers the painting.

1908

- Echoing Les Demoiselles, Braque paints his large Baigneuse.

He then sojourns at L’Estaque, where he produces a series of canvases

that would change the face of modern art: exhibited that autumn in Paris at

the Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler gallery, they cause art critic

Louis Vauxcelles to coin the term “Cubism”. The

forward to the catalogue is written by a friend of Braque, Guillaume

Apollinaire.

- Juan Gris sets up in a studio at the Bateau-Lavoir complex.

1909

- Albert Gleizes encounters Jean Metzinger

and proceeds to explore the use of geometric shapes in his painting.

- Fernand Léger sets up in one of the La Ruche studios

near Montparnasse, where he meets Alexandre Archipenko, Robert Delaunay,

Guillaume Apollinaire, Blaise Cendras, and later Henri

Laurens: a new Cubist group is formed.

- Kahnweiler holds an exhibition of paintings by Picasso, Braque, André

Derain and Kees Van Dongen.

1910

- The Duchamp brothers, Gaston, dit Jacques

Villon, Raymond and Marcel, paint

canvases in the Cubist vein.

- With other Cubists, they exhibit their artworks at the Salon des Indépendants.

Picasso and Braque present oval-shaped paintings.

- A Braque-Picasso exhibition is held at a gallery in Munich: Cubism

transcends borders.

- At the end of year, Ambroise Vollard organises a retrospective

on the artwork of Picasso.

1911

- The Duchamp brothers found the Section d’or

group at Puteaux: Gleizes, Delaunay, Francis Picabia

and others join them.

- Only the Cubists of Montparnasse and Puteaux exhibit their works at the Salon

des Indépendants: Metzinger, Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier, Gleizes,

encouraged by Apollinaire. Likewise for the Salon d’Automne. Their showroom

is the subject of great debate.

- Juan Gris paints his first Cubist artworks, which appeal

to Kahnweiler.

1912

- Gris exhibits his artworks for the first time.

- Picasso starts to use stencils and papiers collés. He leaves

Montmartre to set up on Boulevard Raspail, closer to Montparnasse.

- A Section d’or exhibition

is held at the Galerie La Boétie, featuring the Duchamp brothers,

Braque, Picasso, Gris, Léger, Picabia, Kupka, Delaunay, Gleizes, Metzinger,

Louis Marcoussis, Roger de La Fresnaye and André Lhôte,

among others.

- Gleizes and Metzinger publish Du Cubisme, the first theoretical writing

on the movement.

1913

- Apollinaire publishes a collection of texts, Les peintres cubistes

(aesthetic meditation).

- Picasso, Braque and Marcel Duchamp take part in the Armory Show,

a major New York exhibition that introduces their artwork to an American public.

1914

- Picasso creates a serie of sculptures that take the Cubist issues on reference

to reality to their height: a real spoon tops each version of Verre d’absinthe.

- Braque, Léger, Gleizes, Metzinger, Villon are called to service for

the war.

- Picasso remains in Paris, while Gris settles in Collioure and becomes closer

to Matisse.

1915

- Henri Laurens begins to create Cubist sculptures.

- It is rumoured that Picasso is producing drawings in the style of Ingres.

Braque suffers a head wound and must be repatriated, but does not take up painting

again until 1917.

- Marcel Duchamp, discharged, leaves for New York, where he and Picabia become

major figures of the Dada movement in the USA.

1917

- Braque renews with painting and pursues his investigation of still lifes.

- Picasso paints the drop curtain for the ballet Parade in a Neo classical

style

For references and bibliography : you can consult the French version

of the file Le

Cubisme ![]()

Pour consulter les autres dossiers sur les collections du Musée national d'art moderne

En français

![]()

En anglais

![]()

To know more about the Museum collections: www.centrepompidou.fr/museum

Contacts

Afin de répondre au mieux à vos attentes, nous souhaiterions connaître vos réactions et suggestions sur ce document

Contacter : centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

© Centre Pompidou, Public and Educational Action Unit,

February 2007

Text : Vanessa Morisset

Layout : Michel Fernandez / Florian Tromeur

Translated by Vice Versa

Copyreader : Olivier Rosenthal

Dossier on-line at www.centrepompidou.fr/education

section on ‘Educational Dossiers’ (en)

or at www.centrepompidou.fr/education

(fr)

Co-ordination: Marie-José Rodriguez