Exhibition itinerary

![]() Educational dossiers

Educational dossiers

Exhibition itinerary

|

5 March to 2 June 2008, Gallery 2, Level 6

|

|

|

|

Louise Bourgeois in 1990, behind her marble sculpture Eye to Eye (1970) Photo Raimon Ramis |

From image to sculpture

The role of drawing

Femme-maison, 1946-1947

Quarantania I,

1947-1953

Fillette (Sweeter Version),

1968-1969

Metamorphosis as a principle of the work

The ambiguity of materials, shapes and meaning

Janus fleuri,

1968

Cumul I,

1968

Untitled, 1996

The Reticent Child,

2003

Memory: source and subject of creativeness

Sculpting the psychological space

Precious liquids,

1992

Cell (Choisy), 1990-1993

Red Room (Parents), 1994

Spider, 1997

Born in France in 1911 and residing in New York since 1938,

Louise Bourgeois is one of the major artists of the second half of the 20th

and early 21st Centuries. Her work, which has traversed Surrealism, Abstract

Expressionism and Minimalism, oscillating between abstract geometry and organic

reality, escapes all attempts at artistic classification.

Based on memory,

emotion and the reactivation of childhood souvenirs, Louise Bourgeois follows

a subjective approach, using all types of material and all manner of shapes.

Her personal and totally autobiographical vocabulary is consistent with the

most contemporary of practices, and exerts an influence on many artists.

Organised by the Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne in association with the Tate Modern in London, this landmark exhibition has gathered together over two hundred works – drawings, paintings, sculptures, installations, engravings, objects – produced between 1940 and 2007. Presented in three spaces, it begins in the Forum with a giant bronze and steel spider, never before shown in Europe. In Gallery 2, a chronological display reveals the major works with a special focus on the past decade of the career of this 96-year-old artist, who unremittingly innovates her artistic vocabulary. The Galerie d’art graphique presents “Tender compulsions”, a more intimate exhibition, conceived in the manner of a “cabinet of curiosities” displaying drawings, engravings and small sculptures that indicate the permanence of certain themes and the diversity of the techniques and materials employed.

This document, prepared with teachers in mind, proposes

an investigation of Louise Bourgeois’ work from three key aspects of her

creative style:

- from image (painted, engraved,

drawn) to sculpture,

- metamorphosis as an essential principle of the work,

- memory: source and subject of creativeness, sculpting

the psychological space.

Though a sculptor, Louise Bourgeois nevertheless maintains an attachment to the image, painted, engraved or drawn, by which she began. Drawing has been a consistent practice, a sort of secret diary in which she records her “pensées plumes” [feather thoughts] as she calls them, visual ideas that she captures in mid-flight and fixes onto a highly varied range of substrates. These visual ideas may or may not give rise to sculptures. Through drawing she decants the complex memories and images of her past that emerge into consciousness, called up by intense emotions. Since art and life are indissociable in her view, we can understand the importance of drawing when we look at the artist’s childhood.

Louise Bourgeois spent her childhood in Choisy-le-Roi where her parents ran a tapestry restoration business. From the age of eleven, Louise helped with the job of drawing the motifs. The thread used to restore the tapestries can be metaphorically compared to the line of the drawing. As Marie-Laure Bernadac points out in her book Louise Bourgeois, La création contemporaine [Louise Bourgeois, Contemporary Creation] (Flammarion, 2006, first edition, 1995), her first automatic drawings are associated with primitive scenes of childhood, birth, and maternity. Though less immediate, painting was nevertheless one of the means of expression favoured by the artist up until the late 1940s.

In the early 1930s, Louise Bourgeois attended the School

of Fine Arts and various art academies, including the Grande Chaumière, where

her teacher Fernand Léger detected her vocation of sculptor.

“Painting does not exist for me”, declares the artist, claiming to be attracted

more by the “physical aspect of sculpture” which alone enables her the

expression of emotions, the goal of her artistic approach, releasing and

overcoming fear by giving form to the affect.

In 1938, she met the art historian Robert Goldwater.

They married and went to live in the United States. In her first solo exhibition

in 1945 in New York she presented twelve paintings. In 1947, one of the major

themes of her work appeared in her drawing and painting: the femme-maison [house-woman].

![]() Femme-maison,

1946-1947

Femme-maison,

1946-1947

Oil and ink on linen, 91.50 x 35.50 cm

Whether in the series of paintings and drawings produced in the late 1940s, the marble sculptures of the 1980s, or the large installations of the 1990s, the Cells, the theme of the house-woman is omnipresent in Louise Bourgeois’ work.

In these paintings, which derive their taste for the meeting

of incongruent elements from the surrealists, the women’s bodies terminate

in different types of houses.

In this rigorously vertical canvas, the female

body, lacking arms, carries a grey house with columns on its shoulders.

The grey rigidity of the house contrasts with the bright pink female body

whose outlined genitals resemble a flower. Emerging from the roof of the

house, like a cloud of smoke, is a net-like structure evoking a woman’s hair, to which the artist, who

once had a splendid head of hair, was much attached. “Hair is omnipresent

in Louise Bourgeois‘ early drawings and paintings. Luxuriant, sensual, even

self-erotic, it is perhaps the only irrefutably feminine substance in her

world”, writes Robert Storr, in

“Géométries intimes: l’œuvre et la vie of Louise Bourgeois [Intimate Geometries:

the Work and Life of Louise Bourgeois]” (in Art Press, n°175, Dec 1992). Warm and cool colours, straight and curved

lines, geometrical and organic elements coexist in these images that

are the product of a strange and personal combinatory logic. Marie-Laure Bernadac

sees in “this blend of the geometrical and the organic, of rigidity and malleability,

of architecture and viscerality, (…) the metaphor of her psychological structure” (in Louise

Bourgeois, op.cit. p.64). A psychological structure

built of contrasts.

More than mere feminist propaganda denouncing the overwhelming burden of the home in a housewife’s life, as the titles might lead us to believe, here we find an immense nucleus of inspiration. The house is the ideal receptacle for all memories and, in particular, those of childhood. The childhood home where her family life was very turbulent, due to a flighty father who was often unfaithful to her mother with other women and, much more painfully for the artist, with her young English governess, Sadie.

![]() Quarantania

I, 1947-1953

Quarantania

I, 1947-1953

Wood painted in white with blue and black,

206.40

x 69.10 x 68.60cm

It was not until 1947 that Louise Bourgeois began to sculpt,

creating totemic figures in wood. These figures,

that she would later call “personages”, are

the entities that enabled her to

“exorcise the homesickness” that she experienced

when she left France and her family members.

Always placing her emotional life

at the centre of her art, Louise Bourgeois emphasises: “In the beginning,

my work represented the fear of falling. Afterwards, it became the art of falling.

How to fall without being hurt. Then the art of being here, in this place.”[1] From this

fear of falling that she felt in 1940, pregnant

with her first child, she developed one of the essential themes of her art.

All the “personages” of 1947-49 have in common, according to the artist, “the

fragility of verticality (…) that the superhuman effort of standing upright

represents.” The monoliths that she created during these years are directly

interrelated. A spatial and psychological field of attraction and repulsion

commands them. From the outset, Louise Bourgeois saw sculpture as an interrelationship

with the environment and of the works between themselves.

Lacking bases, the personages were designed to be pushed into the ground

like totems. The constraints of her gallery obliged her to provide them with

bases.

Quarantania I is composed of five figures, all “totems” that she showed separately at her first exhibition at the Peridot Gallery in New York in 1949. In the centre is the Woman with Packages surrounded by several shuttle-women. The shuttle, one of the tools used by her parents in their workshop where they restored Aubusson tapestries, is a formal and emotional element associated with the artist’s childhood. Precariously balanced on the point that fixes it to its base, each female figure here seems nevertheless to support the other and to arrive at a form of equilibrium and harmony. Each member of the group maintains its independence, respecting the territory of those surrounding it, while all together they protect the central figure. As Robert Storr writes: “Strengthened by their thoughtfulness and incapable of falling outside the circle of her peers, Louise Bourgeois’ archetypical protagonist, the precariously-balanced and heavily-loaded woman seems for once to be really sheltered from what she fears most of all.” (in Art Press, n° 175 op. cit.).

Very tall and thin, these wooden silhouettes sculpted by Bourgeois are an affirmation of verticality. Headless and armless, they are made from the wood of the sequoia, which the artist carved with a razor blade. They are also painted in white, a virginal colour for the artist, and in light blue. “Colour is stronger than language. It’s a form of subliminal communication. Blue represents peace, meditation, escape (…) White signifies going back to the start (…)”, notes the artist.

![]() Louise

Bourgeois, Fillette

(Sweeter Version), 1968-1969

Louise

Bourgeois, Fillette

(Sweeter Version), 1968-1969

Latex on plaster (hanging work), 60 x 27 x 20

cm

Private collection

In the early 1960s, Louise Bourgeois abandoned the verticality and rigidity of wood to work with flexible materials. The fluidity of plaster attracted her, as did latex, which inspired works of a biomorphic nature, dealing with the subject of the refuge, the nest. During this period she also produced a great number of works using fragments of the body, often sexual parts.

Playing on the ironic contrast between the title and the

work, Fillette [little girl] represents a penis. The artist was photographed by Robert

Mapplethorpe with the sculpture under her arm, casting a mischievous look

at the camera. Fillette has thus become an emblem of her work, a work

that seeks to maintain fuzzy borders between identities and things.

The shape

of the penis is often seen in her work; its significance has several levels.

There is firstly the erotic significance, since, according

to the artist, underlying everything is the sexual drive and its sublimation

in art. But in her saucy look, the mischievous-artist-girl identifies with

the phallus that she holds in her arms and obliges us to interpret, always

with irony, in feminine terms. Indeed, if the work has the obvious shape

of a penis, it is nevertheless a sort of awkward personage, with a protective covering, feminine, infantile and masculine all

at once. The feminine-masculine ambivalence can also be found in the choice

of materials, the hard plaster and the supple latex covering it.

In the top of Fillette is

a hook by which the sculpture can be suspended from the ceiling.

Seen from

below, the two balls are obviously a reference to testicles, but could also

be breasts, often portrayed by Bourgeois as spherical forms.

In 1966 she produced

a work which could be considered as a companion piece to Fillette: entitled Le Regard [The

Look], an oval mass in latex and cloth evoking female genitalia with a split

in the middle representing both

“the inside of the lips” and the commissure of the eyelids. The eye and

female sexual parts are thus linked together by the artist, in opposition to Freud who associated the glance with the phallus

and the fear of losing sight with castration anxiety.

The fragments of the body – breasts, penis – that repeatedly appear in Bourgeois’ work, all have, according to art critic Rosalind Krauss, the status of “part-objects”, a concept defined by psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. “In the main part-objects are parts of the body, real or phantasied (breast, faeces, penis) and their symbolic equivalents. Even a person can identify himself or be identified with a part-object” (Further to this subject, see the section “Part-object”, in The Language of Psychoanalysis by Jean Laplanche and J.-B. Pontalis, Norton, 1973). In 1934, Melanie Klein introduced the notion of “splitting the object” and of the “good and bad object”. The different phases of psychogenic development according to Klein, centring on the verbs attack, destroy, reconstruct, repair the libidinal object, are those of Bourgeois’ creative act, which is very close to psychoanalysis.[2]

[1] Citations of the artist refer back to the Exhibition Catalogue, which is in the form of a glossary, taking its source in the entries of Louise Bourgeois’ archives. The artist has been keeping her diary since the age of twelve. She writes about her life, her encounters, her thoughts about her art and her private life. Writing alternately in French and English, her thinking is clear and her style incisive. The recent years have been marked by poetic texts, dominated by childhood memories, with alliterations, assonances and other prosodic effects.

[2] Apart from the article by Julia Kristeva, semiologist and psychoanalyst, “Du “petit pois” à la Runaway Girl”, [From the “little pea” to the Runaway Girl] the Exhibition Catalogue also presents the article by Mignon Nixon: “Reconstruire le passé: Louise Bourgeois et la psychanalyse” [Reconstructing the past: Louise Bourgeois and psychoanalysis], entirely devoted to the artist’s relationship with psychoanalysis.

Metamorphosis is one of the essential principles of the work of Louise Bourgeois. It intervenes at several levels: in the sculpture itself and in its interaction with other elements that modify how it is formally perceived and its meaning. Indeed, linking and articulation are the original processes of metamorphosis in Bourgeois’ work.

![]() Janus

fleuri, 1968

Janus

fleuri, 1968

Bronze, gold patina, hanging piece,

25.7 x 31.7

x 21.3 cm

It is above all the work’s intrinsic plastic ambiguity that enables transformation, the passage from one form to another and from one meaning to another. “In perpetual metamorphosis, Louise Bourgeois’ forms provide an inventory of the apparently inexhaustible permutations of sexual oppositions (…)”, emphasises R. Storr (in Art Press, n°175, art. cit.) accentuating the oft-erotic connotations of her work. If Fillette was simultaneously penis and little girl, the flaccid penis of Sleep (1967) underlines the femininity of men, through the formal analogy that the work maintains with the female breast.

In the same year as Fillette, Louise Bourgeois produced other hanging works consisting of human body parts with sexual connotation. Here we have a series of four sculptures in phallic form, with the evocative title of Janus, including Janus fleuri [Flowered Janus]. As the reference to the Ancient Roman divinity indicates, Janus was the god with two faces, one turned towards the past and the other towards the future, the divinity of gates (janua); those of his temple were closed in times of peace and open in times of war. Everything opened and shut according to his desires. It was the bipolar aspect that fascinated the artist in her choice of title. “Janus is a reference to the kind of polarity we represent…The polarity I experience is a drive towards extreme violence and revolt…and a retiring,” writes the artist who also sees in it “a double facial mask, two breasts, two knees.”

The work, in bronze, represents two flaccid penises linked by a central almost formless element that evokes the feminine slit and pubic hair. It is this junctional element whose exuberant matter overflows without precise limits onto the other two parts with their impeccable finish, that makes this work stand out in the series, the adjective “flowered” referring through visual metaphor to the female genitalia as a blossom. Masculine and feminine are once again united in this work with two faces in which, through a subsequent formal shift, penis becomes breast.

As for the modalities of its suspended presentation, it translates for the artist “passivity”, whereas “its interior mass expresses strength and hardness. It is perhaps a self-portrait – one of many”, she notes. Exceeding the limits and the identities of things, Janus fleuri might thus be a self-portrait of the artist, “an undoer of narcissism and of all imaginary identity as well, sexual included," as defined by Julia Kristeva in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (Columbia University Press, 1982, p. 208).

![]() Cumul

I, 1969

Cumul

I, 1969

White marble on wood base,

51 x 127 x 122 cm

The 1960s were for Louise Bourgeois years of maturity in which she experimented with different shapes and materials: plaster, latex, rubber, bronze and marble. After her stay in Italy at Pietrasanta where she went to work with marble, she would use it frequently. This resilient material gives the illusion of the softness of skin.

In Cumul I, nothing seems to stay in place and each shape is destined for perpetual change. Cumul is part of a series that makes reference to clouds, changing elements par excellence, and more precisely the round clouds known as cumulus. “They are clouds, a cloud formation. I don’t see any sexual forms”, she claims. The point of departure for these forms is the sculpture in the shape of a flaccid phallus, Sleep II of 1967.

Here the effervescence of the round white shapes seems to

emerge from a veil of many folds, a Baroque

drapery reminiscent of Bernini (1598-1680),

the great Baroque sculptor who impressed the artist. Beyond the usual reference

to breasts and male genitalia, some of these round forms seem to evoke

the head of a nun whose face emerges – like

that of Saint Theresa in Bernini’s sculpture in Rome (The Transverberation

of Saint Theresa, 1652, Santa Maria della Vittoria)

– from a veil that falls into a multitude of folds.

This same drapery

is found in Femme-maison (1983),

a work in white marble, once again inspired, as Marie-Laure Bernadac points

out, by Bernini. Cumul I heralds the large and impressive latex installation The Destruction

of the Father of 1974.

![]() Untitled,

1996

Untitled,

1996

Clothing, bronze, bone, rubber and steel,

300.40

x 208.3 x 195.6 cm

Metamorphosis is not limited in Bourgeois’ work to a classic

migration of meaning that follows the form. It depends also, as previously

mentioned, on a process essential to her work, the interlinking and articulation

of different elements coming together, like the

pieces of a long visual sentence, to produce a new and unexpected meaning.

Unlike the surrealists, this process does not seek to elicit the astonishment

or surprise of the spectator; it is at the service of the artist’s subconscious,

which gives form to her oldest and most hidden fears and emotions. Art becomes,

in this perspective, a catharsis, an abreaction

of affect in the psychoanalytical sense of the term and, as it is written

in the upper part of Precious liquids: “Art

is the Guarantee of Sanity”.

“Given that the fears of the past are linked to physical

fears, they resurface in the body. To me, a sculpture is the body. My body

is my sculpture,” she declares. Thus, taking a keen interest in the body,

the artist did not omit, during the 1990s, to turn her attention to the clothes

that cover and protect it. This is what she has done in a series of works

featuring clothing and more particularly,

her own old clothes, the last vestiges of a past to be interrogated forever.

Untitled is the association of a black dress with beads and undergarments

belonging to the artist. These elements are hung on a vertical steel structure,

resembling the spool-holders for threads used for tapestry repair in

her parents’ workshop in Choisy-le-Roi.

In fact, the immense polymorphic spool-holder returns repeatedly in her work

and, together with spools and shuttle, is a particular feature of one work: In

Respite, 1993.

Here the spool-holder resembles a sort of tree, onto which

clothes are suspended from disturbing beef bone coat hangers.

The flimsy light-coloured garments, in silk or satin, directly espouse

the bulky bones. The old body that wore them has disappeared and that which

should remain hidden shows itself: the skeleton,

surfacing beneath the skin and flesh that make themselves inconspicuous.

These unusual materials clash or blend with each other and in doing so

reveal themselves: the lightness of satin contrasts with the heaviness

of bone worn down by time and evoking death, the

inalterable metallic structure appears to support the continued existence

of memory.

The linking of the different parts of the work thus proceeds by metonymy (the bone for the human body) and by metaphor (the clavicle for the coat hanger and metal for memory). Thus organised, punctuating the air at different heights, the clothes participate in a strange dance of death.

![]() The

Reticent Child, 2003

The

Reticent Child, 2003

Installation of six elements in fabric, marble,

stainless steel and aluminium,

182.8 x 284.4 x 91.4 cm

Louise Bourgeois’ most recent works refer back in general to the family, the mother-child and father-child relationships and to scenes with a strong erotic charge, often the couplings of adults perceived through the eyes of a child as a protean aggregate of bodies frolicking in a bed, such as in Seven in Bed (2001).

The Reticent Child takes its

inspiration from her relationship with her son Alain. The work, which alludes

in particular to life’s first trauma – birth –, was created for

the Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna. The installation

extends horizontally and presents like a stage maquette.

The pregnancy, birth, childhood and adolescence of her

son are represented. Fabric and marble are the two materials used to create the figures.

There are five figurines in pink woollen fabric and a sixth, lying on a

bed, in skin-coloured marble. Arranged on a metal table, above which is

fixed a large convex mirror, the six personages are reflected in the

mirror. The metamorphosis is

achieved in a spectacular fashion by the deforming mirror, which, depending

on the spectator’s perspective, modifies the perception

of the forms, enhancing the disturbing character of these figures assembled

in a dreamlike scene.

Shadows of the past, enigmatic presences, figures with multiple interpretations follow one another throughout this installation which raises the problem of how to represent time in a plastic work. Here, the choice of the horizontal to signify the succession of events has something which, despite the resolutely contemporary aspect of the installation, recalls an old painting, the famous Tribute Money (around 1427) of Masaccio in which three events of the bible story are represented in the same fresco. Masaccio and his paintings in the Brancacci chapel in Florence return in the gesture of the young man at the end of the work, his head lowered, hiding his eyes, a gesture not unlike that of Adam in Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise (around 1427).

The eye is drawn to the child, diaphanous in marble, reticent, as the title tells us, lying in the foetal position on the bed that it seems to never want to leave. However, as in the dream process analysed by Freud, perhaps the true subject is not that which offers itself as such, but must be sought elsewhere, here, in the organisation of the personages throughout the installation which can be likened to a narrative. The subject is time and its deployment in the scene, in a polyphony of forms and matters, chiaroscuro and colour. The true subject of the work is the inextricable ensemble that is the work itself, this stage on which the representation of life displays itself.

Every work of art simultaneously calls upon thought, imagination, and emotion, interrogating the spectator on several levels. “The arts of drawing are mute, they have only the body to represent the soul, they act on the imagination through the senses, poetry on the senses through the imagination”, wrote Stendhal in 1817 in his History of painting in Italy, emphasising an essential difference between painting and poetry in the effects they produce. The situation is different when emotion, memory and affect are the very subject of the work. This is the case with Louise Bourgeois who incessantly tackles the tasks of giving form to that which is formless and of rendering visible that which escapes visibility and its modalities.

When the subject of the artwork becomes the emotion itself,

the emotion experienced by the artist, as an experience linked to the subconscious,

all must be reinvented, in the most extraordinary of manners. This is what the artist has

done, traversing the different currents of 20th century art,

Surrealism, Minimalism, Informal Art, overtaking them, getting ahead of

them, following at depth the plastic imperative as dictated by her real

and fantasy life, experienced first and relived subsequently, incessantly

questioned in the creative act.

The space of the work becomes unique, a

psychological space, with a logic that borrows the processes of condensation,

displacement and overdetermination from the subconscious. This is how we

must interpret the monumental works of the 1990s, the Cells,

both open and closed, that offer themselves to our view like the crossing

of an inner space.

![]() Precious liquids, 1992

Precious liquids, 1992

Cedar, iron, water, glass, alabaster, fabric,

embroidered cushions, clothing, 427 x 442 cm

In the 1990s, while in her eighties, Louise Bourgeois devoted herself to the creation of these magical chambers, the Cells, in which she gathers objects that are dear to her and which are invested with a strong emotional charge. The Cells are places where she unravels the fabric of her memories and her emotions.

Precious liquids is an imposing

cylindrical installation into which the spectator is invited to enter. It

is a dark enclosed space, composed of a cylindrical cedar water tank, such

as can be seen on the rooftops of New York, and designed for collecting

“precious liquids”.

The liquids are those that the human body produces when

subjected to emotions such as fear, joy, pleasure, suffering. Blood,

milk, sperm and tears are thus the precious liquids that the artist orchestrates

in this space.

At the centre of the strange barrel is an old iron bed surrounded

by posts supporting glass spheres, whose function

is to decant, via the pipes that connect them

to the puddle of water in the middle of the bed, the liquid that rises when

it evaporates and falls back down again when it condenses.

Opposite, a huge man’s coat hangs over the space, enclosing a small child’s garment bearing the inscription “Merci-Mercy”. On the other side are two rubber balls and an old marble sculpture. The installation is a complex work, complex in meaning. The spectator is appealed to by this space, devoid of all human presence yet bearing traces of it, this space in which are inscribed absence, time passing in the dilapidation of the bed and the coat, death perhaps. The strange alchemy of the liquids and the mental construction that the artist attaches to it, transform the space of this work into a psychological space.

In fact, Louise Bourgeois offers an explanation for the significance of the objects. The coat is a reference to the father, a figure of repression, the small garment to the little girl she once was, and the dynamics of the fluids are connected to the feelings of fear that the father elicits. We are here in the midst of “castration anxiety” which, according to Freud, originates in the little girl’s recognition of her lack of a penis and of the existence of sexual differences. The artist has obviously moved on from this phase, but here in this work, with its staging of the fantasy, it is an underlying theme.

![]() Cell

(Choisy), 1990-1993

Cell

(Choisy), 1990-1993

Pink marble, metal and glass,

306 x 170,20 x

241 cm

In Louise Bourgeois’ work, the word cell is a reference to the smallest biological unit that constitutes our bodies as well as to the home, the refuge and the family. And the home means childhood, the first receptacle of life, and the first psychological marks. The artist has produced two series of Cells, one focusing on the senses, the other linked to childhood and memory. “The Cells represent different types of pain: physical, emotional and psychological, mental and intellectual… Each Cell deals with a fear. Fear is pain… Each Cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking and being looked at,” she declares.

Taking an increasing advantage of a polyphony of materials,

Louise Bourgeois now exploits them all: glass, wood, metal, marble and fabric.

Each material has its own story and displays itself in its opacity or transparency,

its weight or lightness, its smooth or rough side.

Cell (Choisy) was the first

of a series of large cages, in which the metal bars are an essential element. They

enable us to see through the piece, at the same time evoking the notion of

captivity. Here is the home of her childhood, the site of all her memories

in Choisy-le-Roi. The house is placed at the centre of the installation.

In pink marble, it might have appeared serene, but it is threatened by the

immense guillotine blade hanging above it. An allusion to France and its

history and to the artist herself in what the psychoanalyst Marthe Robert

would call, like Freud, “the family romance of the neurotic” (Marthe Robert, Roman

des origines and origines du roman [The novel

of the origins and origins of the novel], Gallimard, 1977). For the purposes

of psychoanalysis, each individual creates, from real elements of his or

her childhood, an individual myth in

which reality and fantasies intertwine. This is particularly true in the

case of Louise Bourgeois, who has always used her own family story as a source

of material for her works.

The guillotine shows that “people guillotine each other in a family”. “The past is guillotined by the present,” declares the artist. With advancing age, memories become more and more present, recovered from deep within the individual “prehistory”. The sculpture in itself, a work of volume, physical and tangible, enables the artist to traverse her own past, removing what is morbid and painful. As if conjured up, the ghosts of the past are present in this house, a temple of memories relived and given form in art. The present “guillotines” the past, for art calls the past back to the stage one last time then disregards it.

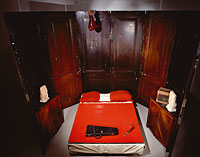

![]() Red

Room (Parents), 1994

Red

Room (Parents), 1994

Detail. Mixed media, 247.6 x 426.7 x 424.2 cm

Reaching further and further back into her past and assuming an increasing amount of freedom, in these two parallel installations, Red Room (Parents) and Red Room (Child), Louise Bourgeois touches upon the “nucleus” of the subconscious, that inexhaustible reservoir of fantasies, and the forbidden territory par excellence, the parental bedroom, associated with what Freud calls the “primal scene” (Urszene), that of sexual intercourse between parents. According to Freud, this act, whether actually witnessed or fantasised, is always interpreted by the child as an act of violence, even as the rape of the mother by the father.

The dominant colour here is red,

a blood red covers the bed. The doors, taken from old theatre boxes, are

in dark wood. The association of red (the colour of passion for the artist)

and black gives these chambers a tragic aspect, in the sense of Greek tragedy.

We can hear echoes of the Oedipal myth and

the inextricable link between Eros and Thanatos. Passion and violence, anxiety

and mystery dominate here.

There is, as always, ambivalence at work. While

the words “je

t’aime”, written in red on the pillow, as well as the child’s toy train and

the musical instrument on the bed evoke peace and serenity in the household,

there is however a strange rubber finger with a pin stuck into it that

emerges from the bed and a sort of red bladder hanging over the same bed

that disturb the ensemble. Threads, spools, needles and pins are a reference

to sewing and her mother’s occupation, while the pricked finger evokes the

young princess of Perrault’s tale, The Sleeping Beauty who,

having pricked her finger on a spindle, went to sleep for one hundred years

waiting for the prince to come and break the spell.

From an art history perspective,

this detail recalls one of Max Ernst’s paintings, Oedipus rex (1922),

in which the pricked finger is a reference to the figure of Oedipus who blinds

himself with a pin when he discovers he has killed his father and slept with

his mother. Here Louise Bourgeois offers her own version of this founding

myth, according to Freud, of the human subconscious.

An oval mirror placed in the installation reflects the bed and increases the feeling of space, a space now uninhabited, in which the beings – unlike the mirror of the nuptial chamber in Van Eyck’s famous painting, the Arnolfini Portrait (1434) – are no longer reflected. The enormous pink shuttle, a further allusion to the parental weaving loom, refers by its size to the child’s vision of objects appearing gigantic. It thus sets up a subtle formal and chromatic interplay with the two red and blue glass balls and disrupts, with irony, the tragic red-black contrast that dominates this piece suffused with the forbidden dimension.

![]() Spider,

1997

Spider,

1997

Steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, silver,

gold and bone,

445 x 666 x 518 cm

The 1990s saw the appearance of a new figure which would become an obsession in the artist’s work, that of an immense spider which she identifies with her mother. Whereas the artist maintained an ambiguous relationship with her father, an immature and fickle man, going as far as rejection, her mother, rational and reassuring, was her friend. Louise lost her mother at the age of twenty-one. A few days afterwards, in front of her father who did not seem to take his daughter’s despair seriously, she threw herself into the Bièvre River; he swam to her rescue.

The Spider series devoted to her mother is, as always, accompanied

by drawings and texts. Writing extends the work of the drawn line, a line

like a thread to be woven into fabric, textual

fabric, that she has nourished since her earliest days. Precise, lucid and

poetic, Louise Bourgeois’ writing presents all the characteristic themes

and obsessions of her work, without detracting from the poignant nature of

her plastic work which always takes the spectator by surprise. Drawing, writing

and sculpture are intimately associated for the artist.

About one drawing

she has written: “The friend (the

spider, why the spider ?). Because my best friend was my mother and

she was as intelligent, patient, clean and useful, reasonable, indispensable,

as a spider. She was capable of defending herself.” (quoted by Marie-Laure

Bernadac, in Louise Bourgeois, op. cit. p.149). The spider spinning its web is associated with

the mother and her work of repairing tapestries. The

artist associates her own work with a web of emotions and memories that

she weaves and unravels and weaves again, like

Penelope, in the course of a lifetime. The artist gives one of her 1999-2000

works a very telling title: I do, I undo and I redo, a

title that reveals Louise Bourgeois’ psychological and creative functioning.

While doing is a reference to the artist’s act, undoing and redoing follow a logic which, according to psychoanalysis, and Melanie Klein in particular, allude to the aggressive impulses of the infant towards the maternal object. Undoing would be destroying the bad mother who is not loving, redoing would be going through the depressive phase associated with guilt and overcoming it by making amends. The artist very often explains the dynamics of her work in terms close to the theories of Melanie Klein (cf. Louise Bourgeois, Destruction du père, reconstruction du père. Ecrits et entretiens, 1923-1997, [Destruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923-1997], French edition, Lelong éditeurs, 2000, p.390). “Artistic work acts as a repair, a restoration in both the literal and figurative sense”, writes Marie-Laure Bernadac on this subject (in Louise Bourgeois, op. cit. p.163).

Nevertheless, as always, the enormous spider that Louise Bourgeois has been creating since 1994 in different forms and presentations remains an ambivalent figure. While the artist sees the figure as beneficent, she does not ignore the fact that it can play the role of a phobic object or be seen as a metaphor for a woman who waits in her web for her male victims to be caught in the trap so she can devour them. The mythological theme of the Three Fates who spin destiny, or of Arachne, a young Greek girl expert in the art of weaving and transformed into a spider by the jealous Athena, are linked to the symbolic character of the representation of the arachnid. Bourgeois offers several versions, some of which are terrifying.

With Spider (1997), she presents both the spider and its handiwork. Indeed this version comes with a cell in the form of a cylindrical cage, inside of which we catch a glimpse of fragments of old tapestries. The yellowish light that illuminates this nocturnal scene is far from reassuring.

Before these immense presences that embody infantile subconscious

fears, despite the positive dimension that associates them with the mother, artwork

here takes on its primary role in Bourgeois’ work, one of replaying fears

to exorcise them and of transforming anxiety into pleasure.

Having taken the path to the Basilica of Saint Peter in Chains

in Rome, where he contemplated Moses (1513-16),

Michelangelo’s renowned marble statue, Freud was deeply moved by the work

and sought to explain his reactions. The feelings of pleasure mixed with

uneasiness that he felt on seeing this work, came from the fact that Moses,

despite his apparent calm, nevertheless maintained evidence of “frozen wrath”,

he writes. Recalling the anger of Moses when he sees his people in adoration

before the Golden Calf, through certain remaining details, the work also

elicits pleasure for the moment “of calm when the storm is over » (cf.

Sigmund Freud, The Moses of Michelangelo,

1914, in Writings on Art and Literature, Stanford

University Press, 1997 ![]() ).

).

Like Freud viewing Michelangelo, Louise Bourgeois also calls

on her spectator to relive old fears associated

with the fury of parental figures, and, through artistic sublimation, to

enjoy the transformation of past anxieties into present aesthetic

pleasures. Her work, in dealing with these emotive moments which constitute

the fabric of aesthetics, understood in the broad sense to mean the science

of the qualities of feeling, touches on what Freud calls Das Unheimliche,

The Uncanny.

It is in the domain of the work of art that psychoanalysis

studies the effects of the uncanny. Certain artworks distance themselves

from the reassuring categories of beauty and arouse feelings of “dread, fear

and anxiety” as Freud points out. Aesthetics “prefer to concern themselves

with what is beautiful, attractive and sublime; that is, with feelings of

a positive nature; and with the circumstances and the objects that call them

forth, rather than with the opposite feelings of repulsion and distress” he

continues, but notes that these two opposing experiences lie within the field

of aesthetics. (Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny,

1919, Penguin Classics, 2003 ![]() ).

).

The work of Louise Bourgeois is at the centre of these

questions concerning the artwork inasmuch as it is a vehicle for reassuring

beauty, disturbing uneasiness, or both at once, calling into question the

classic theories of art in a radical way. In

fine arts as in philosophy, her work is exemplary in its illustration of

the status of an artwork and the reactions it elicits.

![]()

- Galerie 2, Level 6

- Museum, Galerie d'art graphique, Level 4

- Centre Pompidou Forum, Level 0

- Jardins des Tuileries

Guided Tours

Saturdays at 3.30 pm

Conference Un dimanche, une œuvre [A

Sunday, a work]

Precious Liquids, with Elisabeth

Lebovici and Marie-Laure Bernadac.

Sunday 13 April at 11.30 am, Petite salle,

Level -1

Louise Bourgeois Symposium

With Mieke Bal, Jean Frémon, Gérard Wacjman and the exhibition curators:

Marie-Laure Bernadac, Jonas Storsve and, for the Tate Modern, Frances Morris

Wednesday

16 April, 3.00 pm to 6.30 pm, Petite salle, Level -1

City Promenade

Louise Bourgeois and Choisy-le-Roi

Saturday 31 May, 2-6 pm.

> Registration by email promenadesurbaines@yahoo.fr

Cinema

Films by Brigitte Cornand about Louise Bourgeois

Chère Louise, 1995,

50’ ; C’est

le murmure de l’eau qui chante, 2003, 92’ ; La Rivière gentille, 2007,

1.40 pm.

Monday 5 May, Cinema 1, 6-10 pm

Thursday 22 May, Cinema 2, 6-10 pm

Friday 30 May, Cinema 2, 6-10 pm

Disabled Visitors

Saturday 12 April

Listen and see. Tour for the

blind and visually disabled. At 11 am.

Sign language tour at 2.30 pm and Lip reading tour at

11 am for the deaf and hard of hearing.

> Reservation on the Disabled Public page

![]()

Programme for groups and teachers

Exhibition Visit (from nursery to secondary school), scenographic

itinerary for vocational high schools.

Rendezvous for teachers: presentation of

the exhibition Wednesday 12 March at 2.30 pm or 6 pm.

> By

reservation ![]()

To consult the other educational dossiers

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

Contacts

To enable us to better meet your expectations, we would be pleased to

hear your opinions and suggestions regarding this document: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

© Centre Pompidou, Direction of l’action éducative and des publics, March

2008

Text: Margherita

LEONI-FIGINI, schools liaison officer, Education nationale at the DAEP

Translated by Vice Versa Traductions

Copyreader: Olivier Rosenthal

Layout: Michel Fernandez

On-line Dossier at www.centrepompidou.fr/education/ under

’Dossiers pédagogiques’

Coordination: Marie-José Rodriguez