Monographs / Great Figures of Modern Art

![]() Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

Educational Dossiers - Museum’s collections

Monographs / Great Figures of Modern Art

|

|

|

|

| Marcel Duchamp,

Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913/1964 - © Succesion Marcel

Duchamp / Adagp, Paris 2007 . |

Works

• Les joueurs d'échec (Chess Players), 1911

• Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913/1964

• Neuf Moules Mâlic (Nine Malic Moulds), 1914-1915

• Fontaine (Fountain), 1917/1964

• Fresh Widow, 1920/1964

• Rotoreliefs No. 11-12, 1935

• La boîte-en-valise (Box in a Valise), 1936-1941/1968

• Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947

Duchamp’s work, it is fair to say, wreaked havoc in 20th century art. The readymade concept he invented in the 1910s – which self-explanatorily involved choosing existing objects on the grounds that they were aesthetically neutral – opened the door to the most radically avant-garde adventures.

Every movement using everyday objects to startle onlookers (Surrealism, for example), to allude to, bash or even cast a poetic light on consumer society (Pop Art and New Realism, for instance), or to reconcile art and everyday life (as Fluxus) can thank Duchamp for showing the way, overstepping established academic conventions. After Duchamp, the constraints of traditional media vanished and art’s possibilities stretched to absolutely any object, altered or not.

But 20th century art can thank Duchamp for more than

kick-starting a revolution in the materials arena: he also drew the spotlight

on aesthetics’ more complex questions, whence Conceptual Art

ultimately derived in the 1970s. No modern-day artist has probed the concept

of art, asking “when is there art” and exactly what is “enough to produce

art” more frankly than Duchamp did. He was an “intellectual” artist, in the

tradition of Leonardo da Vinci, and opened the door to questions that

Joseph Kosuth later probed.

Duchamp’s work started out as a private pursuit – and indeed most of his readymades got lost during his successive moves or ended up in bins. It was only his recreations that hit the mainstream in the 1960s. In 1964, Milan’s Schwartz Gallery asked him to produce a series of eight original readymade works. That sparked a new thought on a central concept in art history: the term original when applied to readymade art, was something of a misnomer. Duchamp made a point of clarifying this, for example signing “Marcel Duchamp, Antique Certifié” (‘certified antique’) on one of the objects, Le Porte-bouteilles (the Bottle Rack).

Educational anthologies on the collections in the National Museum

of Modern Art for further reading:

- Surrealist Art (in English,

in French)

- Pop Art (in English,

in French)

- New Realism (in English,

in French)

- Conceptual Art (in French)

- The Object in 20th Century Art (in English,

in French)

Marcel Duchamp was the third of six children and the best-known of the four siblings who grew up to become renowned artists. The other three were painters Jacques Villon (1875-1963) and Suzanne Duchamp (1889-1963) and sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876-1918). It was indeed his two elder brothers who introduced him to art.

He went to school in Rouen then moved to Paris, where he continued his studies and attended Académie Julian. His strongest influences, however, were still his brothers and their friends in the Groupe de Puteaux. Groupe de Puteaux was a predominantly Cubist group, counting artists such as Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay, as well as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, the authors of On Marcel Duchamp (1912).

Duchamp soon moved away from the spatial issues that cubists grappled with, to unravel movement. That brought him closer to Italian Futurists (1). One of his paintings, Le Nu descendant l’escalier (Nude Descending a Staircase), made him a name at the prominent 1913 Armory Show in the United States.

He moved to New York in 1915, and then shared his time between France and the United States, where he promoted the Parisian avant-garde (and his friend Constantin Brancusi’s sculptures, in particular).

It was during that period that he created his best-know works, as Le Grand Verre or la Fontaine (Large Glass or Fountain). His interest then shifted towards his other pursuit, chess, which eventually took over almost completely in the mid-1920s.

Surrealism brought him back to art. He organised a number of events on surrealism with André Breton, and his renown rocketed after World War II. In the 1950s, a new generation of American artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who defined themselves as Neo-Dadaists, acknowledge Duchamp as a precursor.

The recreation of his first readymades in 1964 crowned his success, and his works became known around the world.

(1)

See the dossier about Futurism, Rayonism and Orphism (in French). ![]()

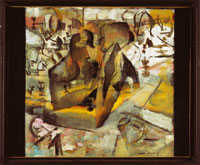

![]() Les joueurs d'échecs (Chess players), December

1911

Les joueurs d'échecs (Chess players), December

1911

Painted in Neuilly, France.

Oil on canvas, 50 x 61 cm ![]()

This painting shows that Duchamp’s early work was influenced by the Parisian avant-garde – which he had met through his two elder brothers, Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876-1918) and Jacques Villon (1875-1963).

The shaded tones and split reality (the pieces strewn across the board’s surface, in particular), give away his interest in Marcel Duchamp. But, if Marcel Duchamp’s pioneers Braque and Picasso were more intent on deconstructing space, Duchamp was more intent on unravelling movement. He also painted Jeune homme triste dans un train (Sad Young Man on a Train) (1911) and Le Nu descendant l’escalier (Nude Descending a Staircase) (1912), two paintings in this same vein, during that phase.

The theme – chess players – and the style are reminiscent of Cézanne’s Les Joueurs de cartes (The Card Players) (1), which is well known for the players’ arms converging in the centre, and for conveying the notion that the game is bonding the two silhouettes. Duchamp used the same arrangement here, and the arms symbolize the involvement and communion between the players.

Duchamp produced six studies to hone this painting, which then, in turn, foreran Portrait de Joueurs d’échecs (Portrait of Chess Players) the next year (1912), which is currently in the Philadelphia Museum. The models were his two brothers, who also played chess often.

Duchamp started playing chess early on and made it onto the French team in the 1920s. Chess then took over to the point of relegating art to the sidelines. In his 1961 autobiography, Man Ray described Duchamp thus: “His mind is alert and chess leaves no hint of the most intense mental activity. Chess was his programme. The competitive aspect of chess interests him less than its analytical aspect, and the possibilities it opens up for invention.”

The intellectual aspect of Duchamp’s future work already shines through this painting’s theme.

(1)

Cézanne’s The Card Players, 1890-95, Orsay Museum ![]()

(2)

Nude Descending a Staircase, Philadelphia Museum ![]()

(3)

Study for Chess Players, Guggenheim Museum, New York ![]()

![]() Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913/1964

Roue de bicyclette (Bicycle Wheel), 1913/1964

Duchamp created the (since lost) original in Paris in 1913.

The Schwarz Gallery in Milan produced this replica under Duchamp’s supervision

in 1964. It is the sixth version of this readymade piece

A bicycle wheel assembled onto a stool

Metal and painted wood, 126.5 x 31.5 x 63.5 cm![]()

Bicycle Wheel is often considered Duchamp’s first readymade. But it isn’t: he affixed the wheel onto the stool so it was not, strictly speaking, an existing object. Duchamp himself indeed describes it as a sculpture on a base, in the same vein as the ones his friend Constantin Brancusi (1) produced.

In a letter he wrote his sister in 1915 from the United States, where he was living at the time, he explained that a readymade (or already-made) was, self-explanatorily, a pre-existing object enshrined as a work of art simply because an artist had chosen it. Conversely, Duchamp explained, he had produced Bicycle Wheel because he enjoyed watching the wheel spinning (explaining the stool). The spinning wheel, he went on, was as enthralling a flames in a fireplace (which he would have used had he had a fireplace). Whether that was a joke or a calculated move is hard to tell.

Duchamp’s famous sense of humour probably shines through this wheel. But the concept underlying it ties in with a recurring theme, movement, which also comes up in Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) and stretches through to his film Anemic Cinema (1925) and his Rotoreliefs (1935). Bicycle Wheel, in other words, seems to reflect a genuine interest in movement and its hypnotic power.

Duchamp picked up the object that became his first real readymade, the Bottle Rack (2), in the Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville in 1914, because of what he described as “pure visual indifference”. His sister signed it a year later as if it had been wrought in an atelier, “based on Marcel Duchamp”. He left these objects behind in Paris, but it was on their account that he retrospectively coined the term “readymade” in 1915.

(1)

- See the Brancusi Workshop, Centre Pompidou, National Museum of Modern Art

![]()

(2)

-

See Le Porte-bouteilles (the Bottle Rack) in the Collections of

the National Museum of Modern Art ![]()

![]() Neuf Moules Mâlic (Nine Malic Moulds),

1914 – 1915

Neuf Moules Mâlic (Nine Malic Moulds),

1914 – 1915

Broken in 1916, reframed by the artist between two panes of glass

A work in three dimensions

Glass, lead, oil paint, varnished steel, 66 x 101.2 cm ![]()

Besides inventing readymades, Duchamp started working on a colossal project that became something of a legend, Le Grand Verre (The Large Glass) or La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even), in the 1910s.

The enigmatic title points to a painting that, in a way, challenges painting history. By using a glass pane, Duchamp breaks loose from the imaginary confines of canvas, replacing them with a transparent (or, otherwise put, transitive) surface. The theme, however, is more traditional (love).

This painting confronts a group of men, the Bachelors, and a woman, the Bride, who, in Duchamp’s words is “stripped bare before the bliss that will debase her”, instants before the virgin reaches the “culmination of virginity” and becomes the wife. Duchamp started working on this painting in 1912, but left it in a “definitively-unfinished” state in 1923 (no doubt adding to the mystery surrounding it).

Neuf Moules Mâlic (Nine Malic Moulds) is one of the studies that Duchamp worked on in preparation for Le Grand Verre (The Large Glass). They belong mostly to the bottom part of the painting, which is “a firm base on solid land”, where males belong. The bride, on the other hand, is floating overhead in a “transparent cage”. The strange objects depicting the men look like moulds, presumably used to manufacture uniform and uniformed males (the gendarme, delivery man, priest and so on). Duchamp describes them as “wombs of Eros”, or desire-producing machines. Fumes rise from the men towards the bride (not unlike steam from a machine). The underlying statement is that there is something mechanical about desire, and that it wraps around and sets on a specific object.

The

Large Glass, Philadelphia Museum of Art ![]()

![]() Fontaine (Fountain),

1917/1964

Fontaine (Fountain),

1917/1964

Ascribed title: Urinal

Duchamp created the (since lost) original in New York in 1917. The Schwarz Gallery

in Milan produced this replica under Duchamp’s supervision in 1964. It is the

third version

White earthenware, covered in glazed ceramic and paint, 63 x 48 x 35 cm ![]()

Fountain is Duchamp’s best-known readymade. Much has been said and written about it, and it has prompted aesthetics specialists to analyse the redefinition of art it triggered.

Duchamp originally bought this perfectly ordinary urinal and submitted it for an exhibition which, its organisers had said, would display anything provided artists helped cover costs. Duchamp was actually one of the organisers and wanted to probe the extent to which this generous principle applied.

Once he had purchased it, he turned it up upside down, baptised it (not un-poetically) Fontaine and signed Richard Mutt (the owner of a large equipment-producing company). So, as it had a name and an author, it had all the extrinsic properties of a work of art. Still, the selection committee turned it down.

When the exhibition opened, Duchamp asked a friend (who was also a rich collector) to ask for Richard Mutt’s Fountain. On learning that it was not on display, this rich collector, who was purportedly intending to buy it, was manifestly outraged. That was how the hype surrounding this Fontaine started. The rest, of course, is history.

After the exhibition, Duchamp published a series of articles on “The Richard Mutt Case”. In them, he wrote some of the most ground-breaking and pertinent statements on art, and replied to the charge of plagiarism that, “Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He chose it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view — created a new thought for that object.”

In Duchamp’s view, artists are not necessarily handymen and, in art, ideas take precedence over creation. The Renaissance’s leading lights would have agreed. They elevated painting to the rank of a liberal art, on a par with astronomy and mathematics. Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, defined art as a ‘causa mentale’.

However, what makes Duchamp’s idea different was that he proffered an object that had none of the intrinsic qualities, such as harmony or elegance, that we usually associate with art. It only has the outward signs of a work of art. It follows a positive definition, a ‘nominalism’ of art.

![]() Fresh Widow, 1920/1964

Fresh Widow, 1920/1964

Duchamp created the original in New York in

1920. The Schwarz Gallery in Milan produced this replica under Duchamp’s supervision

in 1964. This is the third version of this readymade

Assemblage

A miniature French window, wood painted blue and eight squares of black waxed

leather on a wooden plate

Painted wood, leather

79.2 x 53.2 x 10.3 cm

Plate : 10.2 x 53.3 x 1.9 cm ![]()

The title is one of those puns that Duchamp loved. In the United States, most windows open upwards. The rare hinged windows that open inwards are called French Windows. Thus French Window led to Fresh Widow, and the black squares mirrored her mourning.

Beyond the pun, this work probes western painting tradition and Alberti’s definition of paintings as “open windows looking out onto the world”.

Duchamp had this miniature window built and added the squares of leather instead of glass to produce the converse: a closed window, looking out onto nothing. So the eyes linger on the window itself, as it has ceased to be a gateway to somewhere else (unlike Matisse’s 1914 Porte Fenêtre à Collioure (1) looking into the dark light).

Here, the window stands out as an object. And an object that needs to be taken care of: Duchamp left instructions for its upkeep in the concept note: the leather squares, he wrote, are to be “waxed ever morning as you would wax a pair of shoes, so that they shine as bright as real glass shines.”

The interaction between transparency and opacity in Fresh Widow stems from the issues that The Large Glass broaches, and reverts onlookers to their own views.

(1)

Henri Matisse, Porte Fenêtre à Collioure. See for an analysis of this work. ![]()

![]() Rotorelief n°11 - Eclipse totale (Total

Eclipse) / Rotorelief n°12 - Spirale blanche

(White Spiral),

1935

Rotorelief n°11 - Eclipse totale (Total

Eclipse) / Rotorelief n°12 - Spirale blanche

(White Spiral),

1935

Object

A cardboard disk. Colours printed by offset lithography

Diameter: 20 cm ![]()

Rotoreliefs were originally cardboard discs with spiral patterns printed on them, made to be watched whirling on record players. They are “toys” that produce an illusion of volume. Duchamp got that idea after producing Anemic Cinema, an optical-illusion film, in 1925.

If the film was only shown privately, these discs were produced to be sold. Duchamp applied for a patent from the Seine Department’s business court on 9 May 1935 and introduced them to the public in August that year, at the Lépine innovation show. He produced 500 envelopes, each containing a number of models.

Business-wise, the venture flopped in France and in the United States (where he also tried to sell his discs). From an artistic point of view, however, these Rotoreliefs show that Duchamp had his hands in a variety of endeavours: he worked as an engineer and entrepreneur, and was one of the first artists to offer multiple works of art in boxes. It was this idea that later sparked the concept of a box containing objects from his full legacy, La boîte-en-valise (the Box in a Valise).

The Rotoreliefs in the Museum’s collections have been recreated following the last series of discs, which were placed vertically onto powered stands.

![]() La boîte-en-valise (Box in a valise),

1936/1968

La boîte-en-valise (Box in a valise),

1936/1968

Paris (1936) - New York (1941)

A cardboard box covered in red leather containing miniature replicas of works,

69 photos, and painting facsimiles or reproductions, glued onto black folders

Red leather, cardboard, red fabric, paper, rhodoid (or mica)

40.7 x 38.1 x 10.2 cm ![]()

Duchamp was already thinking about producing a box containing his works – or rather texts and a few sketches – back in the 1910s. Those early musings led to La Boîte verte (The Green Box) in 1934. He produced 300 of those, containing mostly his notes for The Large Glass.

After Green Box, he started planning another box containing all the works he had created since the beginning of his career. That was where the idea of an album, so to say, containing images of his paintings, came about. It included Nude Descending a Staircase, Chocolate Grinder and the Nine Malic Moulds, as well as miniature three-dimensional replicas of his sculptures and his readymades (featuring Fountain, naturally). The painting reproductions were black-and-white photographs that Duchamp had coloured himself. In doing so, he created new originals, which he then certified by hand. Coming from the man who invented readymades, this project raises timeless questions about art and about what characterises it.

The wealth of objects it contains makes it a work in its own right: the Box in a Valise, finished in 1941. What makes it unique is the fact that it contains a myriad of works which are both reproductions and originals. Duchamp, in a nutshell, offers up a little portable museum which ties in with his own circular definition of art (it is the museum that makes art art, but it is art that makes a museum a museum). Again, he opened the door to a boundless question for aesthetic theory.

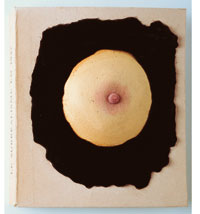

![]() Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947

Prière de toucher (Please Touch), 1947

A breast on velvet, displayed behind glass. Boxed for

the luxury edition of the catalogue of the exhibition "Le surréalisme en

1947", Maeght Gallery, Paris

Rubber foam [latex] glued onto black velvet, cut and glued cardboard

41.8 x 34.7 x 7.1 cm ![]()

This work mirrors the fact that Duchamp hovered near the Surrealists in the 1940s. It was designed for the cover of the catalogue for the Le Surréalisme en 1947 exhibition, which he organised with André Breton at the Maeght Gallery in Paris. It is a fake foam breast, glued onto the board cover. The back of the catalogue counter-intuitively reads “please touch”.

This work, in other words, is an invitation beyond seeing (the traditionally predominant sense in western art) into something more worldly: touching. It beckons a tactile experience akin to the many surrealist adventures that challenged both academic notions and handed-down conceptions.

Yet, beyond this experience and the central role of touch, and still in the surrealist spirit, there is the erotic dimension that shines through all of Marcel Duchamp’s work. Sexuality was a recurring theme in his work, and one often associated with voyeurism. Examples stretch from 1912, when he started working on La Mariée mise à nu… (Bride Stripped Bare…), through Feuille de vigne femelle (Female Fig Leaf) in 1950 (1) or Etant Donnés (1. La chute d’eau, Waterfall, 2. L’éclairage au gaz, Illuminating Gas) in 1946-1966, now in the Philadelphia Museum (2).

-

Female Fig Leaf, 1950, Tate Gallery, London ![]()

-

An image from Etant Donnés: 1. Waterfall, 2. Illuminating Gas, 1946-1966

![]()

1904

Marcel Duchamp joined his brothers in Paris and attended Académie Julian.

1909

He started working on Cézanne-inspired painting. He was close to Gleizes,

Metzinger and other “dissident cubists”, who congregated regularly in his brother

Jacques Villon’s house in Puteaux, outside Paris.

1912

Nude Descending a Staircase was removed from the Salon des Indépendants

and exhibited at the Salon de la Section d’Or, organised by the Duchamp brothers,

in Paris. Duchamp started working on The Large Glass.

1913

Nude Descending a Staircase was exhibited at the Armory Show in New

York. Duchamp emerged as one of the French avant-garde movement’s main exponents.

1915

He travelled to the United States to meet his friend Francis Picabia, and

met Man Ray who became a lifelong friend.

1917

Duchamp submitted his Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists’

selection committee (which he belonged to) using a pseudonym, Richard Mutt.

It was declined, sparking a string of articles explaining the concept: The

Richard Mutt Case.

1919

He returned to Paris and worked with the Dadaists.

1920

He returned to New York. Man Ray, Katherine S. Dreier (a rich philanthropist

heiress) and Duchamp founded an organisation to promote contemporary art by

buying works by young artists. The association was named Société Anonyme,

after a joke by Man Ray.

1921

Duchamp teamed up with Man Ray to publish the first and only issue of New

York Dada (a “dadadate”, as Man Ray put it).

1923

Duchamp abandoned his Large Glass (and rumour had it he was abandoning

art altogether).

1924

He took part in René Clair’s avant-garde film Entr’acte. In the opening

scene, Duchamp is seen playing chess with Picabia on the roof of the Champs-Elysées

theatre.

1926

The Large Glass was exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum. That was when

it was cracked.

1932

Duchamp played for the French Chess team. He and a fellow chess player wrote

and published a book about ending games.

1935

Presented his Rotoreliefs at the Lépine innovation contest.

1938

Produced 300 Boxes in Valises containing miniature replicas of his

works.

1939

Published Rrose Sélavy, a compendium of deliberate spoonerisms and

puns.

1942

Worked with New-York-based surrealist refugees, in particular André Breton,

with whom he organised the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition. For

it, he lined the rooms with two kilometres of intertwined thread.

1947

Duchamp organised the second international surrealism exhibition, Le

Surréalisme en 1947, in Paris with Breton. He produced Please Touch for

the catalogue cover.

1953

Life magazine ran an article on Duchamp, propelling him to celebrity.

1954

The Philadelphia Museum of Art opened, thanks to Louise and Walter Arensberg,

who were friends and patrons of Duchamp and donated their collection. The museum

counted 43 of his works.

1958

Marchand de Sel, the first anthology of Duchamp’s writing, was published.

1959

Robert Lebel published the first essay about Duchamp.

1964

Milan’s Schwartz Gallery recreated 13 lost readymades, with eight copies.

1966

London’s Tate Gallery organised Duchamp’s first major retrospective.

1967

The Paris Museum of Modern Art hosted a Raymond Duchamp-Villon/Marcel

Duchamp exhibition.

1968

Marcel Duchamp died on 2 October in Neuilly, France.

1973

The Philadelphia Museum of Art and the New York Museum of Modern Art hosted

a Duchamp retrospective.

In the French version of the Marcel

Duchamp dossier, you can consult some extracts of texts and a bibliography.

To know more about the Museum's collections and the current artworks hanging,

www.centrepompidou.fr/musee

To consult the other dossiers on the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

Contacts

So that we can provide a service that meets with your requirements, we would like to have your reactions and suggestions regarding this document.

Contact: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

Credits

© Centre Pompidou, Direction de l'action éducative et des publics, March

2007

Documentation, Editing : Vanessa Morisset

Translated by Sté Art International

Graphic Design : Michel Fernandez, Ariane Cock-Vassiliou

Coordination : Marie-José Rodriguez