Itinerary

![]() Educational

Dossiers - Museum's collections

Educational

Dossiers - Museum's collections

Itinerary

|

The Object

|

|

|

| Martial Raysse, Soudain l'été dernier (Suddenly Last Summer), 1963 |

Representing

the Object

The Cubisme experiment

• Georges Braque (1882-1963)

• Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

The

real object subverted

from Duchamp to the Surrealists

• Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

• Surrealism and the Strangeness

of the Object

The

Object in society

American Pop Art and New Realism

• American Pop Art

• The New Realists

Staging

the Object

Personal mythologies

• Joseph Beuys (1921-1986)

• Bertrand Lavier (1949)

The object has run throughout the western pictorial tradition ever since antiquity. But it was in the 16th century that the representation of inanimate objects became quite separate as a genre in itself: the still life, which would then be canonised as the painting of objects posed as if suspended in time and arranged by the hand of the artist.

Skulls, musical instruments, mirrors,

baskets of flowers and fruits seem to enclose the

viewer in the mute world of things. Dutch painting

in the 16th and 17th centuries

was full of tables arrayed with crystalline glasses

and peeled fruit, while the vanitas became

established in France, where a century later the undisputed

genius of the genre would rise to prominence: Chardin.

The still life was to be Cézanne's preferred

realm of pictorial production, since it offers an

inexhaustible repertoire of forms, colours and different

kinds of light. The Cubists would see it as

the genre best suited to conveying the question of

the representation of space in painting. With his

revolutionary Still Life with Chair Caning,

as early as 1912, Picasso brought into the

picture a piece of oilcloth for the caning and a rope

to give material presence to the oval of the chair's

frame. Components lifted from reality therefore sometimes

replace representation and they enter into dialogue

with the painted parts. The object, or rather fragments

of real objects, invade the representation.

But the radical gesture was Duchamp's, transforming the manufactured everyday object into a work of art by means of nothing more than the artist's declaration that it was one. The first ready-mades date from 1913. Since that time, the object has left the picture frame and invaded the real world, presenting itself as such on the stage of art. It would later be deployed in the most unlikely appropriations and assemblages by the Surrealists, in the "accumulations", "compressions" and various "traps" of the New Realists, in the installations of current new objective sculpture, and by way of American Pop Art's simultaneous celebration and critique, which took the consumer society and its objects as the main subject of its art. The object addresses 20th-century art, its status and its boundaries, pushing them further and further.

What this dossier proposes is a perusal of the National Museum of Modern Art's collections through one of the main artistic events of the last century: "the affirmation of the object".

The Cubist still lives are peopled with violins and bottles, pedestal tables and newspapers, glasses and guitars. Devoid of any action, this pictorial genre was ideally suited to the plastic experiments of Braque and Picasso between 1910 and 1914. There, the object is represented in its countless facets and through a diffracting of picture planes whereby it is developed in space. The monocular vision of classical perspective is shattered into pieces by virtue of a multiplication of planes intercut across the surface of the painting.

![]() Cinq

bananes et deux poires (Five Bananas and Two Pears),

1908

Cinq

bananes et deux poires (Five Bananas and Two Pears),

1908

Oil on canvas

24 x 33 cm

Here Braque explores the motif of the fruit bowl, with an explicit reference to Cézanne. It is superfluous to refer to Cézanne's influence on Cubist painting, but Braque does so in a conscious and singular manner. He returns to the motif of the still life and develops it in a spatial dynamic where what has prime importance is the continuity of space rather than the strict definition of the object. The green of the pears chimes with the green of the tablecloth and the ochre of the bananas with that of the wall. The geometrical forms have a resonance with the light and shadows of the space. Braque reminds us that "The painter thinks in shapes and colours, the object is poetics"; he also says that "one must not merely reproduce things. We must penetrate them, become the thing ourselves".

![]() Le

Guéridon (The Pedestal Table), 1911

Le

Guéridon (The Pedestal Table), 1911

Oil on canvas

130 x 89 cm

The motif of the round table was to be a constant in Braque's painting. Only a hint of the table remains: one segment of a circle indicating the outline, while the objects elude us the moment we think we recognise them. The fragmentation of the objects into a multitude of luminous facets which mentally recreate light, creates the sensation of a tactile space in movement. Colour is reduced to greys and brown ochres, a procedure typical of this early phase of Cubism, dubbed Analytical Cubism. The artist stated that the austerity of the colours comes about from a concern to convey space and space above all without there being any interference that might disturb the perception of this.

If 19th-century Naturalism had been obsessed with the "reality of vision", Cubism did not aspire to real vision, but to the artist's mental experience of the world. Thus a new "writing of the real" (Kahnweiler) was developed, put into practice by Braque and Picasso first in the so-called Analytical phase which is dominated by a "reality of conception", to which the representation of the world submits.

On the basis of the papier collés (pasted-paper pictures) invented by Braque in the autumn of 1912 and continued by Picasso, another phase of Cubism began, the Synthetic phase, characterised by a return to reality and another mode of expressing the real. There is a dialogue between the drawn framework and the cut-outs from newspapers selected for their plastic or semantic aspects. The object is conveyed through the breaking up of fragments derived from reality and in an interplay with letters and drawings. Picasso then invented a language of signs recapitulating the object, hence the term Synthetic. He would increasingly insist upon the ambiguity of the representation, the trompe-l'oeil effect, by alternating three different techniques: painting, sculpture and collage.

![]() Verre d’absinthe (The Glass of

Absinthe), 1914

Verre d’absinthe (The Glass of

Absinthe), 1914

Painted bronze with sand and

absinthe spoon

21.5 x 16.5 x 6.5 cm

Verre d’absinthe is the only monochrome example of a series of six, a first cycle of variations by Picasso. Here the form is open towards its interior, which also has to be represented. Between the brown monochrome version and the others the difference in colour seems also to affect the form. But this is only an illusion brought about by the colour being applied at certain points. By means of the colour, sometimes one element and then another comes into the foreground. Verre d’absinthe belongs to Synthetic Cubism through this intervention of colour within the synthesis of planes.

The glass, along with the bottle, is one of Cubism's favourite objects. It brings about transparency and optical diffraction, allowing a widening of the form. Unlike the object as something strange, which it was for the Surrealists, this is a studio object, a familiar object.

As underlined by Werner Spies, the originality of this work lies in the curious conjunction of the glass shaped by the hand of the artist, therefore a represented glass, a real silver spoon, and the facsimile imitation of a lump of sugar. So here we find three levels of reference. "I was interested in the relation between the real spoon and the sculpted glass. In their confrontation", Picasso declared.

Spies further observes that it was a matter of giving the object "the object's maximum experience". The object is not presented as something static, nor within a kinetic perception (the Futurists) which would muddle the form. Picasso reconciles the form and the perceptual richness of a form which is opened up to a space where the various planes of the object "are added up". The sanded side of the outside of the glass echoes the roughness of the sugar which contrasts with the smooth appearance of the perforated spoon. The real object and the art object coexist in a tension which gives a dynamism to the work and to its effectiveness. As Spies writes, the silver spoon emphasises the illusion, namely the reality effect of the representation. We are right at the heart of the glass of absinthe and its function connected with the mythical alcoholic drink. Everything is in place for the water; mixed with the liquor and poured onto the sugar, it will begin the magic ritual.

With his Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), Picasso had already made great advances in the process of desacralising the work of art through the insertion of components taken straight from reality into the painting. The use of collage emphasised this challenge to the canonical representation. The raw materials of reality broke into the representation, but these intrusions formed a dialogue with the painted or drawn parts of the work and the Cubists used them for plastic purposes. Marcel Duchamp went a step further in desacralising the work of art. This desacralisation and its implicit relation to the object was to be redeployed in a new drama of the object, the Surrealist object, on the search for the dream's irruption into reality.

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968)

![]()

The Ready-mades

In 1913, Marcel Duchamp exhibited a "sculpture" titled Bicycle Wheel. Two everyday objects were attached and stuck together by the artist: a bicycle wheel and a stool. Nothing here was the handiwork of the artist, who produced a three-dimensional collage by assembling two ordinary objects.

Duchamp had been a painter to begin with and rebelled against painters, whom he called "turpentine addicts", and against "the retinal stupidity" connected with this art. He pronounced himself closer to the style of Leonardo, and defined painting as a mental thing. His Nude Descending a Staircase caused a sensation in New York and made him famous. Going beyond the nude, with it he sought a method of reducing movement in space.

![]() Porte-bouteilles (Bottle-Rack),

1914 (1964)

Porte-bouteilles (Bottle-Rack),

1914 (1964)

(Séchoir à bouteilles

ou Hérisson, Bottle-Drier or Hedgehog)

Bottle-Rack in galvanised iron

64.2 x 42 cm (diam.)

In 1914, with his famous Porte-bouteilles, bought at a department store, the Bazar de l'Hôtel de ville, Duchamp elaborated the concept of the ready-made: "an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of the work of art by the mere decision of the artist" (Dictionnaire abrégé du Surréalisme, André Breton, 1938).

The hand of the artist no longer intervenes in the work. All skill and all aesthetic pleasure connected with the perception of the work are made void. The creator's traces have disappeared and been reduced to the mere choosing and titling of the object. The title which from the outset names the object most baldly, Porte-bouteilles (Bottle-Rack), will assume increasing importance; later the object would be rechristened Séchoir à bouteilles ou Hérisson (Bottle-Drier or Hedgehog).

Yet the choice of this object was not an insignificant one. Glasses and bottles had invaded Cubist painting, from which Duchamp wished to escape since it was, in his words, like a "straitjacket". Analytical Cubism's bottles and glasses broken down into countless transparent facets were succeeded by the real object, opaque and made of iron, welcoming them with the prickliness of a hedgehog.

![]() Fontaine (Fountain), 1917/1964

Fontaine (Fountain), 1917/1964

Upturned urinal, porcelain

63 x 48 x 35 cm

In 1915 Duchamp left for the United States. Continuing with his ready-mades, he added inscriptions to them, like the one on a snow shovel: In Advance of a Broken Arm. It is only verbal logic that, through humour or puns, transforms the ordinary object into something else: a precipitation of the likely future. Duchamp was to lay increasing stress on this verbal dimension which, by insinuation, involved the mind of the viewer in the perception of the work. The delectation of the eye was succeeded by that of the mind.

His best-known ready-made, the famous upturned urinal rechristened Fontaine, dates from 1917. When it was submitted for exhibition at the Society of Independent Artists, in New York, under the pseudonym R.Mutt, the jury to which he himself belonged rejected it, and the epic success of the ready-mades got under way with this scandal.

The original ready-mades have disappeared and replicas remain which, as Duchamp put it, "convey the same message as the original". In his view, aesthetic criteria alone are not enough to define what art is and what it is not, and it will be the artist who calls into question the limits of art by pushing them further and further. The disappearance of the utility of the object proclaimed by its installation in a museum environment, and the new meaning conferred upon it by its title, would henceforth suffice to qualify as a work of art what had not been so a priori.

Duchamp's radical and innovative approach laid the foundation for a great many interrogations of the status of art in the twentieth century, and for a breakthrough of the object into the domain of the plastic arts.

Surrealism and the Strangeness

of the Object ![]()

In the view of André Breton: "Ready-mades and assisted ready-mades, objects chosen or composed by Marcel Duchamp from 1914, are the first surrealist objects". Where the Dadaist spirit of revolt and provocation had seen Duchamp as one of its most representative figures, the Surrealists too acknowledged his paternity in terms of how they saw the object.

In fidelity to the principle of their aesthetic, which is illustrated by Lautréamont's words: "Beautiful as the fortuitous meeting of an umbrella and a sewing-machine on a dissection table", the surrealist object is the fruit of combining the most unlikely objects that have issued from the encounter of two different realities on an inappropriate level. The sought-after effect is always surprise, astonishment, the sense of strangeness like that provoked by the irruption of a dream into reality. The association of objects made in the name of the free association of words or ideas which, according to Freud, dominate unconscious activity and dream activity in particular.

Since the Surrealists were particularly interested in the object, the Dictionnaire abrégé du Surréalisme offers a panoply of artistic objects: real and virtual objects, the mobile and the mute object, the oneiric object, the phantom object, etc. What unites these different declensions of the object is their unconscious and symbolic charge, the appeal to a surreality which the Surrealists found more real than the real itself.

Man Ray (1890-1976)

A painter and photographer, Man Ray literally illustrated Lautréamont's clarion words from the Chants de Maldoror - "Beautiful as the fortuitous meeting of an umbrella and a sewing-machine on a dissection table" - by photographing the coming together of these objects. Man Ray was a protagonist of the Dada movement, and his strange objects mark the shift in Dada's cherished aesthetic of revolt against fine painting towards the poetic of the strange, the fantastic and the dream, which is Surrealism's, to be made official by Breton in 1924 with his Surrealist Manifesto.

![]() Objet

à détruire (Object for Destruction),

1923

Objet

à détruire (Object for Destruction),

1923

Metronome and collage

23.5 x 11.5 cm

Surrealist avant la lettre, the metronome that has ceased to mark time is one of Man Ray's "objets empêchés" (impeded objects). Similarly as with Cadeau (Gift) (1921), an iron to whose base he had affixed 14 nails which made it impossible to use, here the metronome is made silent and motionless, and set off with the incongruous addition of an eye and a label which subvert the original object and lead towards other spaces suggesting the overdetermined meanings of dream images.

Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966)

![]() Table (The Table), 1933

Table (The Table), 1933

Plaster

148.5 x 103 x 43 cm

Conceived as a piece of furniture, this sculpture, whose principle resides in the strange association of objects, exerts a subtle sense of troubling strangeness upon the viewer. The partly veiled head of a woman and her veil extended into the void suggest by metonymy a body absent from the scene of the representation but potentially part of the table. The strange polyhedron, balanced unstably on the edge of the table, in contrast with the figurative elements of the sculpture, adds to the mystery of the composition. Here we can discern a quality of expectation and dread.

Joan Miró (1893-1983)

![]() L’objet

du couchant (Sleeping Object), 1935-36

L’objet

du couchant (Sleeping Object), 1935-36

Painted carob tree trunk with

metal components,

64 x 44 x 26 cm

On a carob tree trunk painted red, Miró hung pieces of scrap iron found by chance on his walks. These attracted him by some irresistible magnetic force. A metal spring, a chain and a gas burner were meant to represent a bridal couple. When it was made this object was presumed to be a joke, except by Breton, who was gripped by its magical quality and to whom the object was given.

Victor Brauner (1902-1966)

![]() Loup-table (Wolf-Table),

1939-1947

Loup-table (Wolf-Table),

1939-1947

Wood and parts of stuffed fox

54 x 57 x 28.50 cm

The table, whose connection with meals and life-giving nourishment makes it the most familiar and reassuring of objects, is turned into its opposite by metamorphosis into an aggressive and devouring animal. The word loup (wolf), contained in the title, conjures childhood tales and fantasies of being swallowed up and eaten. However, there is a further unsettling of our vantage point in the fact that what this peculiar assemblage shows us is a fox.

Max Ernst (1891-1976)

![]() Loplop présente une jeune

fille (Loplop introduces a young girl), 1930, 1936,

1966

Loplop présente une jeune

fille (Loplop introduces a young girl), 1930, 1936,

1966

Oil on wood, plaster

and collage of objects

194 x 89 x 10 cm

Surrealist objects are not only presented as such by association with other objects. They can also invade the two-dimensional space of the painting, as in this picture synthesising his work, which Ernst returned to twice after long intervals.

The artist is identified with Loplop, the bird at the top, who presents his painting in an effect of distancing which is disturbing both visually and mentally. Max Ernst had already produced pictures in relief, but here it is painting itself which is called into question by the derisory quotation of the picture within the picture.

The painting presented by Loplop is only a simulacrum of painting as emphasised by the painted frame. Inside it is a rough surface, like the rest of the panel, in which real objects replace painted objects. This is a crazy challenge to pictorial mimesis, to illusionism as a whole and to the work of the painter, who is resolutely placed beyond the painting. Objects - a metal wheel, a stone in a net and a horse's mane - impose their reality as objects without the ambiguity of being decorative. They belong to the thematic repertoire of the artist, who thereby declares his creative output to be in the realm of distanciation.

In the United States as well as in Europe, the 1960s opened in the realm of the object. What the pop artists proposed was a return to the real, a reality that they identified with the consumer society, mainly employing its media images simultaneously to decry it and proclaim it. For the New Realists, who defined their art as a "new perceptual approach to reality", the object became a fully-fledged protagonist in their means of expression.

The object as a commodity promoted by the consumer society became established in the 1960s with its language of advertising and its mass media. Already in the late 1950s, artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had reacted against the final gasps of Abstract Expressionism, finding sources of inspiration in the anti-academic spirit of Dada and in the figure of Duchamp. These artists advocated a return to the real, and while Rauschenberg was integrating all kinds of second-hand objects (newspapers, stools, beds, Coca-Cola bottles, etc) into his vast Combine Paintings, Johns was making paintings of the American flag or of shooting targets, these being literal paintings of the object in question.

In the way opened up by these two pioneers, artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine in sculpture, and Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in painting, turned resolutely towards the discredited world of commodities (hamburgers, detergent boxes, Coca-Cola bottles) and new forms of popular culture: advertising, comic strips, film stars and famous politicians, with a vigour that was simultaneously enthusiastic and critical.

Despite the elevation of such objects and images to the status of works of art, it was generally the perverse workings of the consumer society that were revealed by these artists, with humour, irony and unease. Warhol's Campbell's tomato juice packing cases are fake ready-mades, for they were created by the artist, who had the advertising graphics printed on the crates. In the image of market logic, these objects deceive the eye and the mind.

With the American pop artists the object was seldom presented as such. It was reproduced as trompe-l'oeil or in some grotesque form through enlargements altering its meaning, by emphasising the screenprint, sometimes seeming more real than reality itself, to the point of unreality and unease.

Claes Oldenburg (1929)

His version of Pop Art, which is to say art aiming to be within reach of a mass audience, consists in imitating everyday objects connected to the world of food or clothing: commodities that are bought at street stalls or in downmarket shops. Oldenburg's replicas of these objects are enlarged, exposing the materials of which they are made and exaggerating their colours. Giant lollipops, hamburgers, caps and jackets produced in plaster and coarsely painted - drips and all - intrude upon the space around them, blighting it with bad taste.

![]() Pink Cap, 1961

Pink Cap, 1961

Enamel paint on plastered muslin

86 x 97 x 21 cm

Pink Cap was shown as part of a group show together with other objects relating to clothing in New York in 1961. It would subsequently be one of the objects in Oldenburg's shop, The Store, opened by the artist at his studio in ironic imitation of places where such commodities are sold. The spectator-buyer can then, without any mystery, enter the space of production of the work, made by an artist-craftsman working at the very point of sale.

The targets here are the art gallery circuit and museum valuation. There is something troubling about these objects which can no longer be held and handled since they spread out in space. This is the familiar being revealed as strange, assuming vast and enveloping proportions.

Andy Warhol (1930-1987)

Warhol started out as a commercial artist and he is the most representative figure of Pop Art. Both his personality and his work have been a source of fascination. Although he seems the most impersonal and most distant of the pop artists, his work plays upon ambiguity. It was the image of the object that Warhol tackled.

By infinitely reproducing advertising and mass media images through the process of silkscreen printing, Warhol took away their substance, casting it into the hectic domain of the multiple and the banal, yet elevated to the status of a work of art. "I want to be a machine", he declared, legitimising his mechanical process of reproducing the image, the echo of a soulless society which his work represented and implicitly criticised. He made himself the representative of a capitalist society at its peak which was nonetheless troubled by the image of death. Road accidents and electric chairs are the other side of his art.

![]() Electric Chair, 1967

Electric Chair, 1967

Acrylic and lacquer applied to

screen printing on canvas

137 x 185 cm

Warhol subjected the most varied of subjects to the same treatment assumed from a great distance. Drawing always from the mass media repertoire, through the process of the mediatised image which interposes itself between the viewer and reality, he showed the impossibility of reaching the thing itself. Hence the absence of any affect in his works, which denounce the numbing of the modern individual's reality by the society of the spectacle and the commodification of the world.

Thus, the electric chair which, with

the Coca-Cola bottle, is one of the symbols of America,

is presented in terms of a cold and dehumanised image.

This work belongs to the Disaster Series (1963).

The same violent subject is shown in different colours

and, with this aspect of death, it presents the other

extreme of his art, in opposition to smiling faces.

Here the object is replaced by the serial image,

its repetition cold and numbing.

On 27 October 1960, at the Paris home of Yves Klein, in Rue Campagne Première, the official birth of New Realism took place, bringing together the following artists: Arman, François Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Daniel Spoerri, Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé, Jean Tinguely. Their names would be joined by that of the critic who was to be their spokesperson: Pierre Restany. Their declaration amounted to two sentences and announced their programme: "On Thursday 27 October the New Realists became aware of their collective singularity. New Realism = a new perceptual approach to reality".

To these first names would later be added those of César, Gérard Deschamps, Mimmo Rotella and Niki de Saint Phalle. The following year, in a text titled 40° au-dessus de Dada (40° above Dada), Restany situated this movement in a line from Dada and Duchamp.

While demonstrating very different approaches, these artists had a shared interest in the imagery of mass culture and from it they appropriated objects. Raysse went so far as to say: "Prisunic stores are the museums of modern art". But the expression "new perceptual approach to reality" distinguished them from Pop Art and allowed each artist a great deal of freedom. The object as such became a full protagonist in this art which consisted in its appropriation.

While Arman "accumulated" his objects in terms of a quantitative logic which obliterated their singularity, Cesar made a fetish object of cars as sheet metal, "compressing" them to end up with huge parallelepipeds which sat on the ground like polychrome sculptures. Spoerri's "trap-pictures" captured moments of reality by taking the leftovers of a meal which he placed with their dish on the vertical. Raysse developed assemblages in which the anonymous and stereotyped photographic images of women played with the real object in an actual "objective poetry", while Tinguely's absurd and complex machinery, aggregating noisy mechanical objects, set in motion infernal and incoherent mechanisms in the image of our contemporary world.

Arman (1928)

To begin with Arman was an abstract painter, although he has always claimed that his art was a development of painting. He abandoned this practice when he introduced everyday objects into his work. His output is characterised by an ever-changing relationship to the object. Accumulated willy-nilly, or as refuse (the Dustbins series begun in 1959), broken up in the Rages series, burned in the Combustions, becoming detached from a surface such as that of the painting which he called into question, or assembled into huge sculptures, objects mark his work.

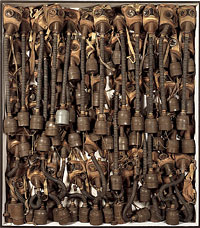

![]() Home Sweet Home, 1960

Home Sweet Home, 1960

Accumulation of gas masks in

a box closed with Plexiglas

160 x 140.5 x 20 cm

In this work, Arman accumulates old objects that are identical, fixes them onto a two-dimensional support and sets them in a box closed by a pane of glass, with the same meticulousness as an entomologist collecting butterflies. But these are not insects. These are not commonplace objects. They are gas masks, arranged differently according to each of the three versions that the artist will give to the work.

The principle is that of the infinite profusion of the same, of the repetition that is apt to spill out of the frame and suggest a sense of all-pervasiveness. The title, intimating the sweet domestic cosiness of the collector engaged in his passionate hobby at home, is in tragically ironic contrast to an object with strong connotations: gas masks, now generally linked in our consciousness to the horror of the Nazi extermination camps. This object, symptomatic of the 20thcentury, is thoroughly restored to its macabre aspect by its accumulation and enclosure in a literal context, the house-as-box, where horror resides.

Martial Raysse (1936)

Martial Raysse often appears as the most prestigious representative of New Realism, to which he belonged in the 1960s. In 1970 the artist was to call into question the ideology of the 1960s rupture with a subtle return to traditional painting, in pastiche form, and by invoking a mysterious and resolutely singular world of mythological references.

![]() Soudain l’été dernier (Suddenly Last Summer),

1963

Soudain l’été dernier (Suddenly Last Summer),

1963

3-panel assemblage: photograph

painted in acrylic and objects

100 x 225 cm

Out of this "picture with variable geometry", operating on discrepant planes and balancing finely between the three registers of photography, painting and sculpture, the real object "suddenly" erupts into the viewer's own space. A straw hat and a towel protrude beyond the painted surface, in a moment of intrusion which recalls that of the title taken from Tennessee Williams. "Suddenly", also like the photographic shutter release which has caught the pose of the young woman on the beach, an anonymous and stereotyped figure from consumer images for sunscreen products or seaside holidays. But on this enlarged photographic image, the painting and the retouching disclose areas which seem to belong to traditional painting: the trompe-l'oeil of the arm, the green shadings on the young woman's legs, the white of the painted sheet.

While celebrating a form of mass imagery, Martial Raysse transcends it with the abrupt irruption of poetry into the here and now of the perception of the work, which does not remain fixed. The photographic model comes out of the frame of the painting, and the real object comes out of the frame of the representation to disturb our perception. Time too seems to be unhinged and suggest several different temporalities simultaneously: the actuality of the photograph as a modern technique of representation joins with the past tense of the pose, "last summer"; the references to traditional painting are answered by the time-disjunction of something breaking in, and the "suddenly" whose meaning here is overdetermined, by the shutter release, by the impression of the image and the perception of the work.

Concealed, painted, freighted with particular psychic resonances, the object was also to be isolated and staged. In these cases, brought into the foreground, the object became a part of the milieu that received it and exhibited it: the museum or the art gallery. Increasingly the work of art is the expression of isolated contemporary projects which have their basis in a personal mythology for which the artist alone has the key to interpretation.

Jean Michel Sanejouand made his first Charges-objets (object-weights) in 1963, works deriving from his anti-paintings. The object is in opposition to painting and presides alone in space. Made up of real objects incongruously assembled with other fragments of objects, these Charges-objets are assembled in such a way that their meaning disappears along with their former use. They aspire to a banality without any signification other than their being there, their problematic presence, their non-sense. All the same, there is an ironic aspect that comes through in these objects weighted with nothing.

For Joseph Beuys, who was close to the Fluxus group, the objects he exhibited (such as Fat Chair, 1964, or Infiltration Homogen for Grand Piano, 1966) are pieces taken from performances he did, where the disguised object took up the whole of the stage. In the late 1960s, Jean-Pierre Raynaud invented his Psycho-objets, while in the 1980s Bertrand Lavier showed his "fridges" and his painted office furniture.

Beuys expanded the idea of art to reality as a whole. His ritual actions aimed to release the plurality of the senses. Art would have a therapeutic virtue and the artist would be akin to a shaman. Objects and materials linked to an entirely personal symbolism anchored in his biography were involved in an art with social aims in a sick society.

![]() Infiltration

homogen für Konzertflügel (Infiltration

Homogen for Grand Piano), 1966

Infiltration

homogen für Konzertflügel (Infiltration

Homogen for Grand Piano), 1966

Grand piano covered in felt and

fabrics

100 x 152 x 240 cm

By associating a piano, a musical instrument and carrier of sound waves, with felt, a material symbolic of life and survival for the artist, Beuys aimed to make this object an energy vector. The piano's sound potential is filtered through the felt. The object is disguised and can be made out behind the fabric which opens it to other sensory experiences. "The two crosses", said Beuys, "signify the urgency of the danger that threatens if we remain silent [...]. Such an object is devised to encourage debate and in no case as an anaesthetic product."

Thus the object becomes increasingly arrayed with symbolic resonances which the artist has to explain since they are particular to him, as is also the case for Raynaud's Psycho-objects. The flowerpot and the square white tile which recur in his work refer respectively to life and death in a cold and increasingly aseptic world.

Bertrand Lavier's work has its place on the pathway that was opened up by Duchamp when he questioned the boundary between art and non art with his ready-mades. This boundary has become an ever finer one and Lavier challenges it with his ordinary objects from everyday life: "fridges" or cupboards with plain, straight lines, impersonal pieces removed from their context and set up in the museum. With his painted objects from the 1980s, Lavier resolves the dilemma between art and non art. Acrylic paint applied in thick layers that parody Van Gogh's brushwork lifts these objects above the mere status of ready-mades. As Jean-Hubert Martin stresses, the paint covers exactly what it speaks of. The object sitting on the ground therefore addresses us with its very ambiguity: it is simultaneously a painting and an object, therefore neither wholly one nor the other.

By employing the superimposition of one object upon another, as for example a refrigerator on a safe, Brandt\Haffner, 1984, Lavier returns to notions of the sculpture and its plinth. Contrary to appearances, Lavier claims to take his inspiration more from Brancusi than from Duchamp, and his subtly organised installations exemplify an interrogation of sculpture itself, by means of the object.

![]() Mademoiselle Gauducheau, 1981

Mademoiselle Gauducheau, 1981

Acrylic-painted metal cupboards

195 x 91.5 x 50 cm

The humorous title brings to mind a female figure in contrast with the object and its strictly geometric form. This surrounds it with a mystery that is redoubled by the pictorial covering of its surface. This metal office cupboard is a banal piece of furniture, completely covered in green acrylic paint, a paint that adheres to the object like a thick elastic skin and gives it a waxy consistency. While the object is insignificant, commonplace and pre-existing its appropriation by the artist, it is the act of a painter which gives it the status of a work of art.

This hybrid piece was shown in the exhibition Cinq pièces faciles (Five Easy Pieces) at the Eric Fabre Gallery, along with two other pieces of office furniture, a Westinghouse refrigerator and a Gabriel Gaveau grand piano. In relation to the other objects in the series and in terms of its installation, as well as the space of exhibition, through its imposing static presence it connects with the kind of sculpture to which the artist lays claim.

Works

• La Collection du

Musée national d'art moderne, published

by the Centre Georges Pompidou, 1986

• La Collection du Musée national d'art

moderne, Acquisitions, 1986-1996, published by

the Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997 ![]()

• L'ivresse du réel, edited collection,

Carré d'art contemporain, Nîmes, 1993

• Denys Riout, Qu'est-ce que l'art moderne ?,

Folio, Gallimard, 2000

• Catherine Millet, L'art contemporain en France,

Flammarion, 1989

• Werner Spies, Picasso sculpteur, Centre Pompidou

Editions, 2000 ![]()

• Art moderne. La Collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne, sous la direction de Brigitte Léal, 2007 ![]()

• Art contemporain. La Collection du Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne, sous la direction de Sophie Duplaix, 2007 ![]()

Links

Educational dossiers on the

collections of the Musée national d'art moderne

•

Pablo Picasso ![]()

•

Surrealist Art ![]()

•

Pop Art ![]()

• New Realism ![]()

Exhibition Itineraries

•

The Surrealist Revolution ![]()

To consult the other dossiers on the collections of the National Museum of Modern Art

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

Contacts

So that we can provide a service that meets with your requirements, we would like to have your reactions and suggestions regarding this document.

Contact: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

© Centre Pompidou, Direction de l'action éducative

et des publics, May 2005

Update : August 2007

Text: Margherita LEONI-FIGINI, professeur relais

in National Education at the DAEP

Artwork: Michel Fernandez, Aleth Vinchon

Online dossier at www.centrepompidou.fr/education/

rubrique 'Dossiers pédagogiques'

Coordination: Marie-José Rodriguez ![]()