Monographs / Great figures of modern art

![]() Educational dossiers – Museum’s Collections

Educational dossiers – Museum’s Collections

Monographs / Great figures of modern art

|

|

|

|

| Impression V (Park), 1911 |

Introduction

An oeuvre still to be discovered

Biography

Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), artist, aesthete

and nomad

THE Kandinsky COLLECTION OF THE Centre Pompidou and THE Kandinsky SOCIETY

I. The formative years and travels, 1900-1907

- Rotterdam, 1904

- Zwei Mädchen (Two Girls), 1907II. From the Blue Rider to abstraction, 1908-1914

- Almanach Der Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider Almanac), 1911

- Impression V (Park), 1911

- Jüngster Tag (The Last Judgement), 1912III. Moscow, 1915-1921

- Einfach (Simple), 1916

- (Untitled) Akhtyrka, 1917IV. The Bauhaus, 1922-33

- Panel for the Juryfreie exhibition, 1922

- Auf Weiss II (On White II), 1923

- Entwicklung in Braun (Development in Brown), 1933V. The final years in Paris, 1934-44

- Composition IX, 1936

- Bleu de ciel (Sky Blue), 1940

reference TEXTS

- Vassily Kandinsky, Regards

sur le Passé, 1913-1918 [Looking

back on the fast 1913-1918], (excerpt)

-

Correspondence Kojève-Kandinsky

(excerpts)

AN Oeuvre STILL TO BE DISCOVERED

Ka the role he played as a pioneer of abstract art during the 1910s and for his essay Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which made him the artist of “inner necessity”. The identification of his art with this invention linked to a quest for spirituality, while it is pertinent, nevertheless gives the illusion of a work concentrated over just a few years, reducing it to this decisive decade. Taken apart and interpreted according to these foreshortened perspectives, for historical and political reasons, it is still difficult to appreciate his work as a whole.

First of all, Kandinsky himself lost some of his work

on two occasions. Just before the war in 1914, as he left Munich for Moscow,

he entrusted his studio and works to his companion, Gabriele Münter. After

their separation, he was never to see these works again, nor are they included

in the monographs published in his lifetime (in 1924 and 1931). They were

not rediscovered until 1956, when Gabriele Münter bequeathed them to the

city of Munich.

Then there are his many paintings acquired by public collections

in the Soviet Union before 1921, which remained inaccessible at least until

1963, when some of them were exhibited during the first real retrospective

devoted to Kandinsky organised by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New

York, almost twenty years after his death.

In addition, the reception of his

work has seen and been subjected to dramatic ideological changes. As a wealthy

Muscovite, he was suspected by left-wing artists of having sympathies with

the White Russians. But having worked in the Soviet Union after the October

Revolution, the Western authorities, and especially the Germans, suspected

him of bolshevism. Caught between two lines of political fire, his art is

best considered as a spiritual emanation free of all material contingencies.

However it is possible that Kandinsky’s art is precisely constructed

in the face of adversity. For example, during

his Muscovite period between 1915 and 1921, Kandinsky, lacking in means

and material comfort, created a series of drawings that today constitute

one of the treasures of the Museum’s collections. Arriving at the Bauhaus

in 1922, he was entrusted with the workshop for mural painting, a discipline

that was far from being his speciality. This was his opportunity to begin

several monumental décors, the entrance hall for the 1922 Juryfreie Exhibition,

and the Music Room of

1931, a recent acquisition of the Musée d’art moderne et contemporain

in Strasbourg. He seized these opportunities, spontaneously contacted

people like Arnold Schönberg, with whom he wished to work.

Thus it is

a body of work, if not complete, at least complex, that this dossier

intends to explore. Here we will pay special attention to the technical

experimentations - linocuts, drawings and painting on glass – undertaken

by the artist throughout his lifetime, with the aim of finding the appropriate form for the content that

he wished to express.

Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), artist, AesthEte and nomad

Kandinsky was born Moscow in 1866 into a comfortable and cultured family. He learnt German from his grandmother, and took lessons in piano, cello and drawing. In 1885, he began to study law at the Moscow faculty, going on to complete his thesis. But when he was just on the point of obtaining a teaching position, in 1895, he decided to break with his legal career and devote himself to art. He then went to Munich to learn painting, and very soon set up as a teacher himself by creating, with other Munich artists, the Phalanx art group. Through this association he met Gabriele Münter, a German-American artist, who was his companion until 1914. With her, he travelled throughout Europe and North Africa and then, in 1906, established himself in Paris for a year. At this time, his works consisted of small paintings, often landscapes in the impressionist style, like a travel logbook, which gained him the reputation of a dilettante in the Parisian milieu.

It was not until 1908, back in Germany, where he was living with Gabriele Münter in Murnau, that his real artistic career began. Although his favourite themes – landscapes, popular culture – remained the same, he treated them in an increasingly abstract manner with a growing autonomy of colours. In 1914, when war broke out, he left Munich to take refuge in Switzerland, then went to Moscow where he remained until 1921. There, he began to write a text, conceived as the companion piece to Concerning the Spiritual in Art, “On Materialism in Art”, which would not be published until 1926 as Point and line to plane. During this period, he painted little, favouring, for material reasons, drawing and works on paper. Then, as the new regime established itself, he devoted his attention to the creation of the country’s new artistic structures, such as the IZO, the state body responsible for fine arts.

Nevertheless, his situation, as much artistic as financial and political, had become precarious. During an official mission in 1921, he decided to remain in Germany with his wife Nina. Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus Movement, offered him a teaching position, which he would occupy up until the school’s closure in 1933 and his departure for France. At this time, his German nationality obtained in 1927 having been revoked, the stateless Kandinsky established himself in Paris. It was not until 1939 that he became a French citizen, in extremis before the start of the Second World War. Until 1944, the Kandinskys led a secluded life in Neuilly-sur-Seine, where the artist pursued his final research objectives.

THE Kandinsky COLLECTION OF THE Centre

Pompidou AND THE Kandinsky SociETY ![]()

THE COLLECTION

The Musée national d’art moderne at the Centre Pompidou together with the Lenbachhaus Museum in Munich and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York are the three international institutions holding the major part of Kandinsky’s works, with the exception of the pieces that remained in Russia when he left in 1921.

The Musée national d’art moderne bought only two works during the artist’s lifetime, in 1937 and 1939. However, in 1976 the museum received the donation of fifteen paintings and fifteen watercolours from Nina Kandinsky, then in 1980 the bequest: the contents of the artist’s studio in Neuilly, which gives the collection its specificity today. The collection has also been enriched with Kandinsky’s correspondence with personalities such as Christian Zervos, director of the Cahiers d’Art, Alexandre Kojève, philosopher and Kandinsky’s nephew, and the magistrate Pierre Bruguière who successfully handled his application for naturalisation, granted in 1939. However, the originality of the collection lies above all in the works on paper from the Moscow period. More recently, in 1994, the Kandinsky Collection of the Centre Pompidou has been the beneficiary of an acceptance in lieu agreement with the art dealer Karl Flinker and acquisitions carried out by the Kandinsky Society. In total, the collection contains more than 100 paintings, as many gouaches, over 500 drawings, sketchbooks, engravings and manuscripts.

The Lenbachhaus Museum of Munich, with the pieces bequeathed

by Gabriele Münter in 1956, has around 123 paintings, 333 drawings and 27 sketchbooks,

while the Guggenheim of New York holds more than 200 works, 150 of which

were acquired from 1930 onwards on the advice of the artist Hilla Rebay who

assisted Solomon R. Guggenheim in his purchases.

In 2008-2009, a large “Kandinsky” exhibition will circulate

between these three institutions, benefiting from the latest discoveries,

especially those concerning Kandinsky’s attachment to his homeland, Russia,

and the city of his birth, Moscow.

THE Kandinsky SociETY

Created by Nina Kandinsky in 1979, the Kandinsky Society is a not-for-profit association (Loi 1901), with its headquarters at the Centre Pompidou. The society unites the directors of the three museums of Paris, Munich and New York, Kandinsky specialists and various personalities designated by Nina Kandinsky. Claude Pompidou was the society’s president from 1979 to 2007.

The society’s vocation is firstly to watch over the integrity

of the work. To this end, the Society has financed the publication of

catalogues raisonnés in continuity with those that the great German Kandinsky specialist, Hans

Roethel, had established. Mrs Vivian Barnett

has published catalogues raisonnés for the watercolours (2 volumes, published

in 1994), for the drawings (in 2006) and for the sketchbooks (in 2007).

Secondly,

the Kandinsky Society has ensured that the testamentary dispositions, preceding

Nina Kandinsky’s bequest in 1980, were respected,

in particular the bequest to the Berne Museum and that of three paintings

to Soviet museums.

The Society also practises a policy of purchase with the aim of completing the Centre Pompidou collection. In 2001, for example, it proceeded with the acquisition of three 1915 watercolours from Mrs Nina Ivanoff, Alexandre Kojève’s companion. It bought the works offered in homage by his colleagues to the Bauhaus in 1926. In 2006, the last purchase was a 1930 watercolour entitled Verdunkeln (Darken). Finally, the Kandinsky Society subsidises the publication of Kandinsky’s manuscripts. It grants bursaries for activities that increase knowledge of the artist’s work.

(The author would like to thank Mr Christian Derouet, curator of the Musée national d’art moderne and member of the Kandinsky Society, for the information he kindly provided for the preparation of this dossier.)

I. THE FORMATIVE years and TRAVELS, 1900-1907

These early years revealed the traits of the artist’s character: an irrepressible nomadic nature and a constant interest for the phenomenon of perception in which, in Kandinsky’s view, colour plays the leading role.

![]() Rotterdam, 1904

Rotterdam, 1904

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard, 23 x 31.7

cm

After his artistic education in Munich and the disbanding of the Phalanx group, Kandinsky undertook a series of voyages, to Holland where he stayed in May and June of 1904, to Tunisia, Italy, Switzerland, Paris and Berlin, with frequent trips back and forth to Moscow and Odessa. These voyages presented an opportunity to break with the academic practices learned at art school and to create paintings from nature. These consist of small landscapes, a little like postcards, but with the picturesque removed to the benefit of an exercise on the perception of reality.

Here we have a small sketch representing more or less

faithfully the port of Rotterdam. Kandinsky probably did not value

it highly: it appeared in his catalogue of small painted sketches, but

remained forgotten in a chest, where it was rediscovered in 1980 in the

cellar of his apartment in Neuilly.

This sketch gives us a glimpse of the

painter’s preoccupations.

Although at this time his painting style seemed close to that of the neo-impressionists,

such as Signac, whom he had exhibited with the Phalanx group, the port

of Rotterdam is painted as if it could be any port, without the slightest

identifying feature. It is undoubtedly because Kandinsky turned away

from what was offered before his eyes. He would

soon cease to paint from nature, creating works in which colour was invested

with a primordial function: to preserve the memory. As he explains in the

first lines of his autobiography, through an example going back to his

childhood, colours are what one remembers best.

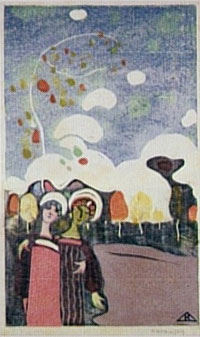

![]() Zwei Mädchen [Two

girls], 1907

Zwei Mädchen [Two

girls], 1907

Linocut, 22.5 x 13.7 cm

The first catalogue raisonné of Kandinsky’s work, published by Hans Roethel in 1970, was dedicated to engraving, giving an idea of the importance that the artist accorded to this technique he practised from 1903 on. His first wood engravings are in black and white, then certain are coloured, echoing the traditional Russian art style he encountered during a trip through Russia when he was still a law student. Like Zwei Mädchen, these engravings bear witness to a taste for schematic representations, evoking a symbolistic world, that would never really leave him.

By using the lino engraving technique, he

managed to fully integrate the central element of his preoccupations, colour.

Indeed with lino, more flexible than wood, it is possible to superimpose

the printing of several plates, each with its own colour. In addition,

for each proof, the colours were changed, creating a unique piece each

time.

II. FROM THE Blue Rider TO abstraction,

1908-1914 ![]()

From 1908 on, Kandinsky’s painting ceased to be that of a dilettante, making its way towards an invention that would prove determinant for the history of painting: abstraction. Supported by a theoretical basis, the works of this period moved further and further away from reality, and, to the question that he formulated in one of his texts – “what must replace the object?” – Kandinsky replied with the impact of colours and lines.

![]() Almanach Der Blaue Reiter [Blue

Rider Almanac], 1911

Almanach Der Blaue Reiter [Blue

Rider Almanac], 1911

Study for the cover of the Almanach Der Blaue

Reiter

Watercolour, gouache and Indian ink on paper,

29 x 21 cm

Back in Germany, Kandinsky became one of the main protagonists of avant-garde painting. In 1911, with Franz Marc he put together “a sort of Almanac with images and articles created exclusively by artists”. The objective was to show that all art forms, however different they might be – painting, music, but also popular arts, children’s drawings – tended to move in the same direction. Because for Marc and Kandinsky, “the question in art is not that of the form, but of the artistic content”.

The Almanach Der Blaue Reiter is a reference to the horsemen of popular mythology. For Kandinsky, the rider is a metaphor for the artist: “The horse carries the rider with strength and speed. But it is the rider who guides the horse. Talent will bring an artist to great heights with strength and speed. But it is the artist who directs his own talent.” (Reminiscences). In this sheet, which is one of a series of eleven studies made by Kandinsky for the cover of the first Almanach, the horse and rider are shown in mid-leap across the page, just as the artist leaps across the distance that separates him from the art to come.

![]() Impression V (Park), 1911

Impression V (Park), 1911

Completed 12 March 1911

Oil on canvas, 106 x 157.5 cm

In this canvas – a further step along the path to abstraction – we can see two riders, one in the centre wearing a blue cape (a veil?) and the other in beige over on the right, as well as two figures sitting on a bench. However these iconographic landmarks dissolve into a mass of coloured splashes and black lines that punctuate the image rather than describing any forms.

The painting is dominated by the red triangle in the centre, installed between two flat blue and green zones in the bottom part, while the black lines indicate a sort of itinerary for the gaze. The subtitle, “Park”, which might place this work in continuity with the landscapes Kandinsky had painted up to this point, constitutes no direct reference to exterior reality. In a letter to a friend, the artist explains that the “subtitles are not there to define the content of the painting. The content is what the spectator feels under the effect of the colours and shapes”.

Consequently, the park is no more than an indication for expressing a more complex content, according to a pictorial rhetoric that Kandinsky formed in the same year. In his work written in 1911, Concerning the Spiritual in art, he defined three types of painting, the “impressions”, the “improvisations” and the “compositions”. Whereas the impressions depend on an exterior reality that serves as a point of departure, the improvisations and compositions depict images arising from the subconscious mind, the “composition” being the most developed from a formal point of view. Therefore, as we can sense when we look at Impression V (Park), the impressions question the phenomenon of perception “interpreted in a more active manner, as a common act of the sensing subject and the object sensed, an act that blends them and in which one is modified by the other”. (Catalogue Kandinsky: oeuvres de Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) [Kandinsky: the works of Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)] Centre Pompidou, 1984, p. 115).

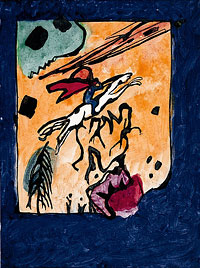

![]() Jüngster Tag [The

Last Judgement], 1912

Jüngster Tag [The

Last Judgement], 1912

Reverse glass painting

Water paints and Indian ink on glass, 33.6

x 45.3 cm

The technique of reverse glass painting,

which consists in painting on the underside of a sheet of smooth or corrugated

glass, was discovered by Kandinsky in the summer of 1908. The painter held

a deep interest for this typical form of Bavarian folk art traditionally

practised in families – and to which he devoted himself with his

entourage – even undertaking research to discover its origins.

This technique interested him not only as an expression

of popular culture, but also because it enables effects of transparency,

brilliance and moiré impressions, depending on the paintings used. Between

1909 and 1913, he completed 33 reverse glass paintings. To protect them,

all these works were framed. Here, Kandinsky also painted the wooden frame.

In Jüngster Tag, this technique

enabled the artist to orchestrate a booming concert

of colours, dominated by variations of yellow. Compared, in Concerning the

Spiritual in art, to “an ear hurt by the shrill

sound of the trumpet”, colour expresses here the pandemonium of the

apocalypse, in reference to the trumpets that, in the biblical text, announce

the hour of the Last Judgement. However, in a wider sense, it reminds us

to what extent Kandinsky was attached to the musical model and, in particular, the notion of composition such as it had been

overturned by Schönberg.

In the first letter Kandinsky addressed

to the musician on 18 January 1911, he established a connection between

their works characterised by the importance given to “dissonance”. As Schönberg

composed his music on the principle of disharmony, so Kandinsky constructed his paintings from a series of coloured

shocks, here yellow and blue, which express

the battle against the chaos of which, according to Kandinsky, all creative

acts are the product.

For the analyses of other works by Kandinsky from this period, consult the educational dossier devoted to the Birth of Abstract Art (French only): Naissance de l’art abstrait.

Long neglected by Kandinsky specialists and by the artist himself, no doubt for political reasons, the period of his return to Moscow prolonged the years of his passage to abstraction and saw the birth of works and writings of an equally important force.

![]() Einfach [Simple], 1916

Einfach [Simple], 1916

Watercolour on paper, 22.8 x 29.1 cm

“Drawings for other times”: this is how the drawings of the Moscow period were referred to in the catalogue of the exhibition dedicated to these years (Musée d’art moderne et contemporain, Strasbourg, 2001). Completed during the war that was succeeded by the Bolshevik revolution, these drawings belong to a context barely favourable to art. Kandinsky had been forced to return to his homeland, where the political and economic situation was difficult to bear. Nevertheless, he must have felt these works had some importance, since he took them with him when he fled Moscow in 1921. And if he failed to show them immediately afterwards, it was undoubtedly because as an exile, whether in Germany or in France, his situation was never really stable.

Einfach, with its austerity and radical dissociation of lines and colours, bears witness to the richness of his production during this time. In his quest for simplicity, Kandinsky radically drew the conclusions of the principles established with the passage to abstraction and, above all, achieved a level of gestural control which, while recalling oriental calligraphy, announced an art that would not appear until the 1950s, Informal Art.

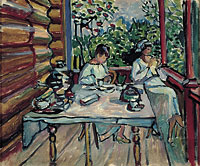

![]() Untitled, Akhtyrka, 1917

Untitled, Akhtyrka, 1917

Oil on canvas, 27.5 x 33.6 cm

This small intimist canvas, a sort of return to the summer of 1917, exemplifies one of the functions that Kandinsky attributed to painting: fixing the memory. Compared with his early post-impressionist landscapes, the recording of memories here is more methodical, especially due to the black rings that delimit the shapes. The scene represented took place on the property of Kandinsky’s cousins, close to Moscow, where he was staying with Nina after their marriage. Under the veranda, Nina, wearing a white bonnet, is making the most of a sunny afternoon with her sister. In sum, more than a problematic return to figuration, this painting, with its lack of detail, is quite simply a matter of the affective. Back once more in a Russian setting, he was fifty years old and starting a new life.

In 1921, Kandinsky was director of the physical-psychological department of the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences, a structure set up after the revolution. With the artistic climate deteriorating, an official mission to Germany offered him the opportunity to flee his country. A teaching position at the Bauhaus enabled him to pursue his work, even though his position as an abstract painter, in a school that was moving closer and closer to industry, was contested.

![]() Panel for the Juryfreie exhibition, 1922

Panel for the Juryfreie exhibition, 1922

Maquette

Gouache on black paper, 34.7 x 60 cm

From 1908 on, Kandinsky created works that had nothing to do with easel painting, such as the “scenic compositions”, musical theatre pieces for which he wrote the texts, created stage designs, choreographies and music. In 1911, he decorated the interior of Gabriele Münter’s home in Murnau, painting the furniture and balustrade with stencils. Then in 1914, he created the decorative panels for the New York apartment of Edwin Campbell, founder of the Chevrolet Motor Company. However, it was above all at the Bauhaus, in his capacity as master of the mural painting workshop, that he created his monumental works. On his arrival in 1922, he was asked by Walter Gropius to design a project for the entrance hall of a contemporary art museum which would be presented at the Juryfreie exhibition in Berlin.

Working with his students, Kandinsky painted immense canvasses where fluid lines and coloured forms composed a joyous symphony on a black background. The motifs are simplified, announcing the notion of geometrisation that he adhered to during his years at the Bauhaus. Of this décor, nothing remains today but the maquettes presented by Nina Kandinsky to the Musée national d’art moderne, in gouache on a black or brown ochre background, which served as models for the reconstruction created for the opening of the Centre Pompidou in 1977. Several years after the completion of this décor, in 1931, Kandinsky created for another Berlin exhibition, the Bauausstellung, a “music room”, a multicoloured ceramic ensemble. The maquettes and the 1975 reconstruction can be found today at the Strasbourg Musée d’art moderne et contemporain.

![]() Auf Weiss II [On

white II], 1923

Auf Weiss II [On

white II], 1923

Completed in Weimar, February-April 1923

Oil on canvas, 105 x 98 cm

A canvas from the Bauhaus period that the Kandinskys had hung in their dining room in Dessau, Auf Weiss II is the rework of a 1920 canvas and its theme of intercepting diagonals. However, it also recalls certain paintings of the 1910s that presented the confrontation of pictorial elements, a gigantomachy of lines and colours, like the events taking place on the canvas.

Here we witness the tension between the two diagonals emanating from an almost square background, the whiteness of which gives the painting its title. On this note, we are reminded of Malevitch’s white squares, but also of what Kandinsky himself said of his backgrounds: I learned to struggle with the canvas, to recognize it as an entity opposed to my wishes (=dreams), and to force it to submit to these wishes. At first, it stands there like a pure, chaste maiden, with clear gaze and heavenly joy—this pure canvas that is itself as beautiful as a picture. And then comes the imperious brush, conquering it gradually, first here, then there, employing all its native energy, like a European colonist who with axe, spade, hammer, saw penetrates the virgin jungle where no human foot has trod, bending it to conform to his will (Reminiscences).

In Auf Weiss II, the whiteness of the pure canvas is enhanced by the white background, a whirlpool of forces arising from its surface. Due to this centripetal movement, these forces are organised into a duality of black lines. For, unlike the other gigantomachies and his previous Auf Weiss, Kandinsky achieved here a general clarity due to the simplicity of the components, as if his struggle with the canvas had ended in the realisation of his wishes.

![]() Entwicklung in Braun [Development

in brown], 1933

Entwicklung in Braun [Development

in brown], 1933

Canvas painted in Dessau after the closure

of the Bauhaus, 20 July 1933

Oil on canvas, 101 x 120.5 cm

Development in brown is a sombre painting, completed in Berlin at the time of the closure of the Bauhaus. Deprived of its subsidies, the school was forced to close in the summer of 1933. This moment was rendered even more difficult for Kandinsky since the Nazis had demanded his departure from the school.

The Bauhaus was thus a chapter of Kandinsky’s life that closed in a climate of anxiety, which the weighty brown of the painting expresses. We can see the different superimposed planes in a monochrome brown motif, like a series of doors closing. In the centre, remains a luminous coloured space. We do not know whether this represented for Kandinsky the definitive end of an era or if it indicates, in spite of everything, a flicker of hope for the future.

V. The final years in Paris, 1934-44 ![]()

In Paris, where he spent the last eleven years of his life, Kandinsky painted and drew prolifically, putting together an important body of work in which the common factor is the inspiration of images from biology, forms resembling embryos, larvae or invertebrates, a minuscule population embodying the living.

![]() Composition IX, 1936

Composition IX, 1936

Oil on canvas, 113.5 x 195 cm

Composed of multiple diagonal bands of colours and small shapes that resemble embryos as much as crustaceans [1], this canvas earned Kandinsky criticism for not sufficiently articulating the background and the shapes. Nevertheless, it is one of the rare large format canvasses to which Kandinsky once again applied the name of “composition”. In Concerning the Spiritual in art, this is what he calls his most accomplished paintings. He completed only ten in all throughout his entire career. Composition IX therefore seems to have been held in great value by the painter and when the French government purchased it for 5000 francs rather than the 100,000 demanded, he felt quite humiliated about it.

This complex canvas is in fact one of the two works that the State purchased from Kandinsky during his lifetime. It shows his new inspiration in pastel and acidic colours, like a hymn to life. Moreover, the painting established a link with artists of the younger generation such as Miró with whom he associated in Paris, placing him back in the centre of issues of artistic interrogation at this time, dominated by Surrealism.

[1] For a precise analysis of the biomorphic figures and their source in the paintings of the Paris period, see Vivian Barnett’s study “Kandinsky and science: the introduction of biological images in the Paris period”, Kandinsky in Paris, Guggenheim Museum, 1985.

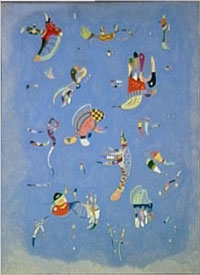

![]() Bleu de ciel (Sky

Blue) [1], 1940

Bleu de ciel (Sky

Blue) [1], 1940

Oil on canvas,

100 x 73 cm

In the final years of his life, Kandinsky renewed himself, as exemplified by this painting with its blue monochrome tendency. As in Joan Miró’s work, The Siesta [2], the background appears like a vibrant matrix, the source of a world of new and poetic forms.

Here, multicoloured hybrid beings, curious animalcules in the process of formation, float in the air. Their lightness is an invitation to think that, for Kandinsky, the mystery of creation, which he had previously represented as a struggle, had been appeased. The former confrontations of colours have given way to the blue that evokes the freedom of the dream, a notion that has never ceased to inspire artists. After Miró and Kandinsky, it would be Yves Klein’s turn to celebrate the artistic potential of the most immaterial of colours.

[1] It is not known whether the title of the painting is due to a problem of language or whether it is in fact a voluntary poetic effect on Kandinsky’s part.

[2] For an analysis of this painting, consult the educational dossier (in English) Surrealist Art.

Vassily Kandinsky, Regards SUR LE passÉ, 1913-1918 (exCERPT)

[Looking back on the past, 1913-1918]

Paris, Hermann, edited by Jean-Paul Bouillon, 1974, pp. 116-117

Painting is a thundering collision of different worlds, intended to create a new world in, and from, the struggle with one another, a new world which is the work of art. Each work originates just as does the cosmos - through catastrophes, which, out of the chaotic din of instruments, ultimately create a symphony, the music of the spheres. The creation of works of art is the creation of the world.

Thus, these sensations of colour on the palette (as well as in the tubes, which resemble men with powerful minds but of modest appearance suddenly revealing, in urgent situations, their forces hitherto kept secret, and causing them to act) will convert themselves into spiritual experiences. These experiences will then serve as the point of departure for ideas of which I became aware [ten or twelve years]* ago [and which then began to assemble themselves to culminate in the book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. This book wrote itself, rather than I writing it.] I transcribed isolated experiences which, as I remarked later, had an organic link between them. I had the feeling, stronger and stronger, clearer and clearer, that [in art things do not depend on] the “formal” but on interior wishes (= content) which [delimit the domain of the] formal.

This was a big step forward – to my great shame, it took me a long time to take it – resolving entirely the problem of art on the basis of an inner necessity [to be able] to overturn at every instance all the known rules and limits […].

*The passages in square brackets correspond to the modifications of the 1913 text made by Kandinsky in 1918 in the Russian version of this same text.

CorrespondEnce KojÈve - Kandinsky (exCERPts)

Texts translated from Russian by Nina Ivanoff, Les

Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne,

Special Issue Archives, 1992, pp. 160-163

Dear Uncle Vassia,

I received your seven watercolours in perfect condition. I will deliver them personally at the beginning of the month of October [to the Galerie de France] to avoid any misunderstanding.

I opened the parcel immediately and was struck by the painting (n°432, 1931) “Fleckig”. I think it is one of your best works (watercolours). Once again something completely new. I can’t explain at this moment what constitutes this newness, but one can feel it immediately. Exteriorly, this painting manifests itself by a certain absence of rectilinear geometry in the figures. One gets the impression that the “creative impetus” finds itself cramped in the presence of forms that have been created before and become rigid in their traditionalism – this impetus explodes them from the inside – the colour spills out of the drawing. To the violence of this creative force correspond the vivid and succulent, almost vulgar colours. At first glance, this painting struck me by its definite relation with certain works of Picasso. Afterwards, I realised that this “resemblance” is based in fact on the force, the frankness and intensity of the painting’s content. This is so typical of Picasso’s works (real and serious). Each time, I am astonished by your capacity to continually discover new forms for your painting. In this, only Picasso could compare himself with you. But unlike him, you never allow yourself the role of ham actor. Yes, in your paintings, there is more tact, more good taste and intelligence and perhaps also skill. Nevertheless, this great quality sometimes becomes a flaw as well; often, and sometimes also with justification, you are reproached for being too concerned with reason. I myself think that some of your works are more illustrations of your theory of painting than they are spontaneous paintings. In this you resemble Leonardo da Vinci.

As far as the other paintings are concerned, they are certainly beautiful. It is true art, like all that you do. But, in my opinion, they are overshadowed by painting n°432. They are all endowed with a traditional structure. Even though you have created it yourself, it is already rigid. One gets the impression that it has not come organically from the artistic content of the painting, but that it replaces this content. The painting resembles in this case a combination (quite remarkable and fine, but without genius) of pre-fabricated forms. And it is not by chance that some of these paintings resemble the watercolours of Klee, of this master of Kleinkunst and of all sorts of “virtuosities”. This is not, of course, a reproach, since no painter can maintain in all his works the highest level of his creative force and spontaneity (even Rembrandt who comes the closest to this ideal did not accomplish it entirely). And you merit this reproach less than anyone. But I wanted to remark on the difference between n°432 and the six other paintings …

Thank you very much for the watercolours and the letters that you sent for me to Berne. I have already written to you that because of the current conditions in Germany, I cannot correspond directly with my Swiss bank. I am therefore obliged to disturb you.

I want to ask you another favour. I was hoping to obtain a book published in Paris through a local bookshop, but without success: the French do not ship to foreign countries. I thought I would buy it myself when I came to Paris, but as you know we didn’t go. This book is indispensable for my teaching. Perhaps you will have the opportunity to pass by the rue Vavin. If you do, please go to Ortet-Roussel, 1 rue Vavin and ask them to send me immediately the first volume of “L’Art aujourd’hui” (Art Today) by carriage forward. If this is not possible, perhaps you could pay for it yourself and let me know how much it cost you. I will reimburse you immediately. I would be extremely grateful to you. I’ve been trying to obtain this book for over a year already.

I found your “criticism” of my watercolours very interesting; you have a very fine sense of perception, this doesn’t happen very often with people who have “thinking heads” which is why I particularly appreciate it. In this you distinguish yourself from “non thinking” people and above all those without sensitivity: these people see no life and not even an artistic sense in my austere works whereas you keep a place for them due to my “past” (as you say). You said: “they were living but they have already started to become rigid”, this is why [...] enough of them. I don’t know, maybe it will be like that. But until now, when I paint things so serious, everything in me is strained to the limit. Here I need a very great inner impetus: the character, the size, and the place of each of these austere forms defines itself each time according to an “inner dictation”, a sort of “vision” and I, I have the impression that such an impetus is not only necessary but also impossible in the case where the forms are rigid.

Many people say that my austere works are also cold. There are Chinese pastries that are hot on the outside (when taken straight from the oven) while inside, there is ice cream. My austere works are like these Chinese pastries but the inverse: cold on the outside, flaming hot on the inside.

So this is my self-defence. Write to me and tell me with total frankness what you think of my work.

Perhaps we will see you in Paris at Christmas. Maybe even before in Germany? In Dessau? That would be nice.

I embrace you and Nina send you her regards.

Your Kandinsky

1866

- Birth of Vassily Kandinsky in Moscow. (Nina Kandinsky insisted

that Vassily be written French-style with a V.)

1885

- He enrols in the Moscow law school.

1889

- First trip to Paris.

1892

- Marriage to his cousin Anna Chemiakina.

1893

- At the university, Kandinsky presents his dissertation

on the legality of worker’s wages.

1895

- He refuses a teaching position at the University of Dorpat

(Estonia, today Tartu) to devote himself to art.

1896

- He moves to Munich.

1900

- Kandinsky enters, as a student, the school of fine arts

in Munich.

1901

- Foundation of Phalanx, an association which is both an

art school and a place where exhibitions are held.

1902

- Meeting with Gabriele Münter.

1903

- Closure of Phalanx and beginning of a series of voyages.

1906

- Beginning of a trip to Sèvres that would last one year.

1907

- Kandinsky exhibits a hundred or so works in Angers.

1908

- Summer in Murnau in the Bavarian Alps with Alexis von Jawlensky.

This period marks a turning point in his work.

1909

- Back in Munich, with other Munich artists he founds the

Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM) association.

-

He writes “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”.

1910

- Meeting with Franz Marc with whom he creates, the following

year, the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter).

1911

- On January 1, Kandinsky goes to a concert by Schönberg.

He writes to Schönberg to tell him how closely he shares, as an artist,

his preoccupations. It is the beginning of a rich epistolary relationship.

1912

- Publication of his work Concerning the Spiritual in

Art.

- Publication of the Almanach Der Blaue Reiter.

1913

- Publication in Berlin of the German version of Rückblicke (Reminiscences),

an autobiography.

1914

- Kandinsky leaves Germany for Switzerland then goes to Odessa

and Moscow.

1917

- Meeting and marriage with Nina Andreyevskaya.

-

After the revolution, he

becomes involved in the creation of new structures for artistic education.

1918

- He works for IZO, a national body concerned with fine arts,

where he works with Rodtchenko, and teaches in the national art studios

in Moscow.

1920

- Participation in the XIXe State exhibition held in Moscow.

1922

- Move to Germany and teaching at the Bauhaus in Weimar.

Kandinsky forms friendships with Paul Klee and Joseph Albers.

1925

- The Bauhaus moves to Dessau, construction of the school,

and the Master Houses.

1926

- Publication of Point and Line to Plane,

written a decade before in Moscow.

1927

- Beginning of his correspondence with Christian Zervos,

director of the Cahiers d’Art. He obtains German nationality.

1929

- Solomon Guggenheim and his advisor, the artist Hilla Rebay,

visit Kandinsky in Dessau and begin their collection.

-

Exhibition in France

at the gallery Zac in Paris.

1932

- The Bauhaus moves to the suburbs of Berlin and closes one

year later.

Late 1933

- The Kandinskys move to Neuilly-sur-Seine.

1939

- Kandinsky obtains French nationality.

1942

- He paints his last large canvas and subsequently concentrates

on small works on cardboard.

1944

-Kandinsky dies on December 13.

1956

- Gabriele Münter bequeaths to the city of Munich the contents

of the studio that Kandinsky had entrusted to her when he left Germany

in 1914.

1963

- First retrospective of Kandinsky’s work organised by the

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

1981

- Death of Nina Kandinsky in Gstaad. The Mnam gains possession

of the contents of the Paris studio that she had bequeathed the previous

year.

Exhibition catalogues

- Vassily Kandinsky. Le Salon de musique de 1931 et ses trois maquettes originales [The Music Room of 1931 and three original maquettes],

Musée d'art moderne et contemporain de Strasbourg, 2006

- Kandinsky, retour en Russie, 1914-1921 [Kandinsky,

return to Russia, 1914-1921], Musée d'art

moderne et contemporain, Strasbourg, 2001

- Kandinsky, collections du Centre Georges Pompidou,

[Kandinsky, collections of the Centre Georges Pompidou] Musée des beaux-arts,

Nantes, co-publication Centre Pompidou/RMN, Hors

les murs collection, 1998 ![]()

- Kandinsky

: œuvres de Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) [Kandinsky:

the works of Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)], Centre Georges Pompidou, 1984

Texts by Vassily Kandinsky

- Point et ligne sur plan : Contribution à

l'analyse des éléments de la peinture,

Paris, Gallimard, 2006

- Point and line to plane. Mineola NY, Dover Publications,

1979

- Du Spirituel dans l’Art et dans la peinture en particulier,

Paris, Gallimard, 2005

- Concerning the Spiritual in Art. MTH Sadler (translator).

Mineola NY, Dover Publications,1977

Online version: http://www.mnstate.edu/gracyk/courses/phil%20of%20art/kandinskytext.htm

- Regards

sur le passé et autres textes : 1912-1922, Paris, Hermann, 2003

- “Reminiscences,”

in Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, Volume One (1901-1921), ed.

Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vargo. Boston, G. K. Hall & Co., 1982,

pp 369-370

- Kandinsky : du théâtre,

[Kandinsky : on theatre] Paris, A. Biro, Société Kandinsky, 1998

- Kandinsky-Albers.

Une correspondance des années trente [Kandinsky-Albers.

Correspondence in the 1930s], Cahiers du Musée national d'art

moderne, Special Issue/Archives, December 1998 ![]()

- Correspondances, textes Schoenberg-Busoni, Schoenberg-Kandinsky [Correspondence,

texts Schoenberg-Busoni, Schoenberg-Kandinsky] Geneva, Contrechamps, 1995

- Vassily

Kandinsky : correspondances avec Zervos et Kojève [Vassily

Kandinsky: correspondence with Zervos and Kojève], Cahiers du musée national

d'art moderne, special issue/Archives, January 1993 ![]()

Personal accounts

- Nina Kandinsky, Kandinsky

et moi, [Kandinsky and I] Paris, Flammarion,

1991

Essays on Kandinsky

- Christian Derouet, « Kandinsky-Delaunay : un échange de lettres

en avril 1912 »,

[Kandinsky-Delaunay: an exchange of letters in April 1912] Cahiers du

Musée national d'art moderne n°73, automne 2000

![]()

- Nadia

Podzemskaia, « Kandinsky entre les sciences humaines

et l’art »

[Kandinsky between human sciences and art], Cahiers du Musée national

d’art moderne n°68,

Summer 1999 ![]()

- Marcella

Lista,

« Les "compositions scéniques" de Kandinsky », [Kandinsky’s

“scenic compositions”] Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne n°63,

Spring 1998 ![]()

- Annette

et Luc Vezin, Kandinsky et le Cavalier bleu [Kandinsky

and the Blue Rider], Paris, Pierre Terrail, 1991

Educational Dossiers

- Vassily Kandinsky: Jaune,

rouge, bleu, 1925 (Yellow, red, blue, 1925 – French

only) ![]()

- La

naissance de l’art abstrait (The Birth of

Abstract Art – French only) ![]()

To consult the other dossiers on the collections of

the Musée national d'art moderne

In French

![]()

In English

![]()

To know more about the museum collections ![]()

Contacts

To enable us to better meet your expectations, we

would be pleased to hear your opinions and suggestions regarding

this document.

Contact: centre.ressources@centrepompidou.fr

Credits

© Centre Pompidou, Direction de l'action éducative

et des publics, March 2008

Works of Vassily Kandinsky © Adagp, Paris

2008

Text: Vanessa Morisset

Translated by Vice Versa Traductions

Copyreader: Olivier Rosenthal

Graphic design: Michel Fernandez

Coordination: Marie-José Rodriguez